April 21, 2004

ASNE's Diversity Study: Looking for Answers

Why do America's newspapers remain so white despite 25 years of effort to have them be more reflective of the communities they cover?

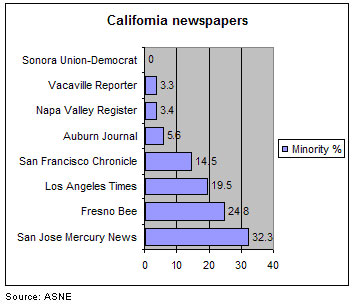

ASNE's annual hiring survey, released yesterday, reported that the percentage of minority newspaper journalists working in 2004 inched up 0.4 points to 12.95 percent - 100 people in absolute numbers. This can be seen as good news by  those who for whom any progress is better than none, but even they agree the overall number is woefully small. Worse, the bulk of minority journalists are concentrated in larger, urban papers, while many smaller newspapers remain lily white and even some larger papers in heavily minority communities lag the demographic changes happening around them. (See chart for examples).

those who for whom any progress is better than none, but even they agree the overall number is woefully small. Worse, the bulk of minority journalists are concentrated in larger, urban papers, while many smaller newspapers remain lily white and even some larger papers in heavily minority communities lag the demographic changes happening around them. (See chart for examples).

What is the problem? Is it a pipeline issue? In other words, are their insufficient minorities in journalism programs? Is it a pay issue? Are those minority journalism (and communications) students opting out of journalism at graduation for more lucrative starting positions in other industries? Is it a retention issue? Are minorities leaving then newspaper business faster than they can be hired?

Let's look at these three issues: The pipeline, attracting minority graduates to newspapers and retention.

The Pipeline

No one tracks journalism school enrollment and entry-level newspaper hiring more closely than Lee Becker, a professor at the University of Georgia's journalism school. Each year, Becker and his colleagues compile reports on who is attending journalism schools and how new journalism graduates are faring in the job market.

Becker said, in an article for the Freedom Forum, that it is "a myth that there are not enough minority applicants to alter the face of America's newsrooms." He told me yesterday in an interview: "There are more minority students looking for newspaper jobs than are able to get them. So, it's not simply a matter of an inadequate supply."

Becker said, in an article for the Freedom Forum, that it is "a myth that there are not enough minority applicants to alter the face of America's newsrooms." He told me yesterday in an interview: "There are more minority students looking for newspaper jobs than are able to get them. So, it's not simply a matter of an inadequate supply."

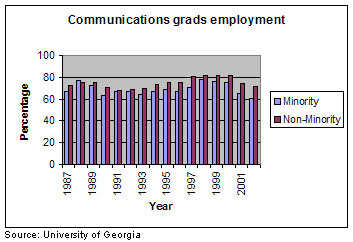

Newspapers reject some minority graduates, though, because they do not meet the criteria by which entry-level hires are judged, said Becker, and as a result white journalism school graduates continue to be hired at a higher rate than minority graduates, as they have for the 15 years Becker has tracked hiring. (See chart).

"Basically," he said, "if you can get the minority graduates to look just like the non-minority graduates in terms of some key things - their internship participation, their participation in the campus newspaper and their specialized socialization in news editorial journalism - they get hired at the same rate as non-minority students, not higher, at the same rate. The problem is minority students are more likely not to have those features, those characteristics than are the non-minority students. So, when the playing the field is leveled in that regard, the hiring appears to be color blind."

The uneven playing field derives in part from the characteristics of the universities many minority journalism students attend, said Becker.

Keith Woods, a Pointer Institute group leader who writes regularly on diversity issues, expanded on Becker's point.

Many minority students attend "historically black colleges, Indian universities or universities in the Southwest that serve principally Latinos," said Woods in an interview, "smaller programs, sometimes with weekly or monthly or no newspaper at all through which they can gather clips, and they're not getting the number of internships in those small programs that they need to be getting." (Asian journalism graduates, by comparison, "come into the industry come through the big programs in the country," Woods said.)

Woods recalled reading a column by Leonard Pitts, the Miami Herald writer who just won a Pulitzer for commentary, in which Pitts said he is "teaching journalism and running into kids who don't know what they need to know to do get themselves prepared for the daily journalism."

Becker said the newspaper industry doesn't tolerate young journalists who can't - to use a phrase I heard, and used, in many discussions about hiring when I worked at the San Francisco Examiner - "hit the ground running." Unfortunately, many minority journalism grads from smaller schools aren't able to do that, he said.

"Maybe they went to a university where the opportunities for them at the student daily weren't very great," said Becker, "or maybe they didn't feel welcome or maybe at that point in their careers they're weren't advised that that was important or maybe just made bad decisions. All of those are possible."

Of course, lack of preparation - by journalism school graduates of all colors - could be overcome with additional professional training, but that is not a component of the newsroom ethos.

"This is not an industry where there's a lot of investment in on-the-job training, particularly not for entry level people," Becker said. (Note: The newspaper industry invests only an equivalent of 0.7 percent of payroll in training, one-third what other U.S. industries spend.) "This is an industry where people are expected they day they walk in the newsroom to be able to do the job. … So, part of the obstacle is that not all of these students are up to that and so the industry can either address that or if it continues to uses those things as the screen I think it is going to make slow progress."

Becker pointed out that "many, many of the entry-level jobs are at very small newsrooms where if you have someone who you've hired that can't go out on the evening she or he was hired and cover a city council meeting, that's a big problem. … So, it's very hard for the industry to pass over someone who is able to do the job for someone who needs more investment, more training. The data suggests that's part of the issue."

Of course, the gap between newsroom expectation and academic preparation affects more than minority journalism graduates. Woods sees it a critical industry problem.

"Journalism education is an issue across the board," he said. "This is not a minority issue. Print journalism needs to communicate more strongly what it wants from the academy as we are getting lots of kids across the racial and ethnic spectrum that aren't ready. But, like everything else, when you cut by race and ethnicity it's going to hurt people of color more because they're in the minority to begin with and in many cases have greater needs. … The problem is at crisis level and I don't know that we're acting like it's at crisis level."

Attracting minority graduates to newspapers

Becker argued that the pipeline is swelling with available talent - 29 percent of all fall 2002 enrollees in journalism and mass communications programs were minorities, about half of them African American.

Of course - as Woods pointed out - many, if not most, do not intend to become newspaper journalists even though they may be studying some form of journalism in college.

"There may in fact be 29 percent minority enrollment in college journalism programs, but, like their white counterparts, a fairly small percentage of them are interested in print journalism," he said. "If you cut those numbers that way, you discover that the pipeline for journalists period, rather than folks who are going into public relations, for example, is at an alarmingly low number whether you're a person of color or whether you're white."

Both the industry and universities "need to get credible and meaningful numbers to compare on this issue so they can have a conversation that's more than just opinion," said Woods.

"You go into the classrooms any day of any week and you ask the students in there how many of them intend to be daily print journalists, you might be lucky to get a couple of hands to go up," he said. "And when you cut our numbers that way, then minority journalists will be severely slashed form the pool."

In his Freedom Forum paper, Becker reported numbers that show the newspaper industry is not doing a good job of recruiting even those minority graduates who are thinking about becoming print journalists.

"In 2001," he wrote, "only one in five of the minorities who sought a job with a daily newspaper - again to pick one example - actually took a job with a daily. Three in 10 took another media job. One in five took a job outside the field of communication. And one in five was unemployed six to eight months after graduation. Of those who actually got an offer, only half took the daily newspaper job."

The current newspaper job market is rotten for everybody (the number of employed newspaper journalists fell 500 positions to 54,200 in 2004, ASNE reported, continuing a nearly 20-year trend of more-or-less stagnation), but it's worse for freshly graduated minorities.

"The gap between the level of full-time employment of minority graduates and their counterparts increased to more than 10 percentage points," Becker reported in his latest survey (of 2002 graduates).

Indeed, minorities are not alone in being able to secure newspapers jobs - the same Becker survey found that "six to eight months after graduation, only half of the journalism and mass communication bachelor's degree recipients were working in the field of communication. The ratio has not been this low since 1992."

That kind of statistic sends a sobering, stay-away warning to any bright minority university student intent on finding a well-paying, rewarding career.

Retention

One area in the newspaper industry where parity exists between minorities and whites is retention - they both quit the business at the same rate, 5 percent (although there have been recent years, 2001 for example, in which more minorities left newsrooms than joined them).

However, as Woods pointed out, since hiring minorities is harder than hiring whites, when they leave the industry their departure has more of an impact.

"You got to consider that if the retention rate is exactly the same it is worse for people of color," he said. "In order for it to be equal, it would have to be proportionate. If you lose 10 percent of 100 and you lose 10 percent of 1,000, you have a different kind of a loss."

A study done in 2003 for ASNE found that "lack of professional challenge and limited opportunities" were the two primary reason minority journalists leave newspapers. Other findings offer a harbinger of a difficult future for efforts to diversify newsrooms:

Between "one-fifth and one-third" of minority journalists "do not expect to remain in journalism over the long term … a much stronger likelihood to leaving the field than white journalists.""The issue of advancement opportunities proved far more salient to journalists of color than to white journalists. For white journalists, the issue of advancement opportunities ranked last among the reason they might leave the field." (Emphasis added.)

Culture as a cause if minority journalist disenchantment

I have to wonder how much affect the defensive, destructive nature of most newsroom cultures has on attracting and keeping good minority journalists.

The Readership Institute's work examining newsroom culture finds that, on average, newspapers have workplace atmospheres that are unwelcoming to change, are disdainful of those who think differently than the norm and are intolerant of people who go against the grain. A minority reporter in a nearly all-white newsroom, one with a likely even whiter management structure, is by definition change, difference and not the norm.

As Woods pointed out, minorities quit newspapers for many of the same reasons as whites - lousy bosses, for example (the No. 1 reason most people quit their jobs) - but "there are other reasons, not necessarily different reasons, but maybe a broader spectrum of reasons" that apply to someone who looks, talks and thinks a bit differently than most other people in the newsroom.

Cultural change in newsrooms could go a long way to producing a change in color as well.

Links

![]() ASNE Newsroom employment drops again; diversity gains

ASNE Newsroom employment drops again; diversity gains

![]() ASNE Diversity in U.S. newspaper groups

ASNE Diversity in U.S. newspaper groups

In March, 200, to mark the 25th anniversary of ASNE's call for newsroom integration, we released an assessment report at the National Press Club in Washignton DC--the results of a two-year study sponsored by the Ford Foundation--"Diversity Disconnects: From Classroom to Newsroom." http://journalism.utexas.edu/faculty/deUriarte/diversity.html It was the first study of its kind and included a national survey of intellectual diversity in print and broadcast newsrooms (as oppposed to integration, which is just about numbers.) As we noted, few newsrooms in the nation are integrated. Even fewer are diverse. It also discussed the number of and various studies on newsroom and academic environment. We believe it offers useful information related to this issue.

Posted by: Mercedes Lynn de Uriarte on April 23, 2004 01:27 AMI have 14 years experience as a college-level journalism educator, and 11 years experience at an advisor for the campus newspaper. I work at a suburban college which is predominantly white, with a small journalism major (90 students) within the English department, a separate communications studies department with an electronic communications track (350 students) and a new interactive multimedia major (35) students. We send students into journalism internships and jobs from all three majors, and our percentage of graduates entering newspaper jobs is higher than the national average (28% vs. 11%).

I find that few of my black and latino students can afford to put in time at the campus newspaper, so they find themselves poorly positioned to compete for paid professional internships. Many cannot afford unpaid internships. Our lower income students, who are disproportionately students of color or from immigrant families, have the highest loan encumbrances and work-study requirements.

Conversely, some of our top journalism students come from more affluent backgrounds and are attending our state school on merit scholarships. Some of them graduate without any loans at all. They are better positioned to take advantage of low-paying or non-paying preprofessional opportunities.

I can empathize with them, because I am a black woman with a journalism degree who ended up in public relations because I couldn't afford the newspaper jobs available to me. When I came out of NYU's MA program in Journalism in the early 1980s, the entry-level newspaper jobs that were available did not cover the cost of my student loan payments. In addition, they were in areas that would have required me to buy a car.

Finally, some of the local newspapers here hire our students as interns, and may keep them on as staff reporters, but they are stingy with full time jobs and benefits.

For all of these reasons, I meet a number of students of color who are interested in journalism but find it an impractical pursuit. With the current economic downturn, I'm seeing that same anxiety in non-minority students as well.

I have some ideas about how to address these problems, but that's another conversation.