April 26, 2004

Son of a Bush!

What gets said about and what gets shown of the war in Iraq - and who gets to say it or who gets to show it - was the topic for newspaper ombudsmen on Sunday, with photos of caskets receiving more universal support than a common cuss phrase.

Michael Arrieta-Walden of the The Oregonian took on the argument over publishing pictures of dead U.S. soldiers and came down on the side of the First Amendment.

His column quoted Paul McMasters of the First Amendment Center:

"The combination of Pentagon restrictions and press interpretations of just what the public will bear is a potent combination when it comes to determining whether the face of war is realistically depicted . . ." he says. "Newspapers, especially, have a duty to show all aspects of a war, its ugly side as well as its public policy side." (Emphasis added.)

Gary Trudeau blew off most of B.D.'s (now an officer in Iraq) left leg in Doonesbury at the beginning of last week and by end of the week B.D. was screaming "son of a bitch!" as a doctor sawed through the limb.

Some newspapers scrubbed the strip entirely (too much "graphic, violent battlefield depictions," said one), others ran it and got praised for doing so and some truncated the expletive ("son of a ...," gee, what does that mean, Mom?).

Minneapolis Star Tribune's Lou Gelfand didn't mince words in favor of publishing the strip: "Gary Trudeau is bringing the obscenity of war into our living rooms. His detractors would say it should not come in the guise of a comic strip. In whatever state it arrives, society will be better off."

Ironically, Mike Needs of the Akron Beacon Journal, which altered the words in the offending panel, used the phrase "son of a bitch" to describe what had been edited out. He supported the content of the strip but suggested it belonged more appropriately in editorial pages "It's unfortunate," he wrote, "the comic strip isn't still located on the editorial pages, where the itch to change the wording wouldn't have occurred. That way, the emphasis could have remained on what's really important, the casualties of war."

Finally, Elsa McDowell, Charleston Post and Courier, which also sanitized the phrase, said "a number of readers have made clear in their previous comments that they are offended by visions of war atrocities," she added that no readers of the paper "registered complaints about the strip's content."

Reporting on war without reporting on the deaths resulting from that war is incomplete journalism that doesn't give readers the full story.

How will those newspapers who thought the Doonesbury cartoon "too graphic" treat those inevitable veterans who return home from Iraq minus a limb or two? Will photos of these damaged men also be unwelcome in their hometown papers?

April 25, 2004

Bush to Journalists: Gotcha!

Jay Rosen wove an excellent essay at Press Think exploring the ramifications of the president's belief that the press -- journalism -- doesn't represent the public.

Rosen quotes a Ken Auletta article:

"And the reporter then said: Well, how do you then know, Mr. President, what the public is thinking? And Bush, without missing a beat said: You're making a powerful assumption, young man. You're assuming that you represent the public. I don't accept that." (Emphasis added.)

In the comments to his essay, Rosen clarifies this point as separate from the partisan positions of a politically liberal (or conservative) press. Says Rosen:

"When Bush says to journalists 'you don't represent the public,' it means a bit more than reporters are unrepresentative, or their views unlike the views of most Americans. I believe Bush is challenging the very notion that journalism is conducted in the public interest, that the public's right to know depends on the press finding things out. That's quite different from "journalists are liberal, Americans on the whole are moderate to conservative," which is not the point the President is making-- even though he probably agrees with that too." (Emphasis added.)

At the root, says Rosen (again quoting Auletta) is Bush's belief that "we don't accept that you have a check and balance function. We think that you are in the game of 'Gotcha.' Oh, you're interested in headlines, and you're interested in conflict. You're not interested in having a serious discussion and, and exploring things."

Read the whole thing.

N.Y. Times: Off the Record

Here's a key section from Daniel Okrent's explicative column on why the New York Times is not the nation's paper of record - nor does it want be:

"Katherine Bouton, deputy editor of the paper's Sunday magazine, said: 'We understand now that all reporting is selective. With the exception of raw original source material, there really isn't anything "of record," is there?' Reporter Stephanie Strom noted that 'we certainly aren't the paper of record for leaders of the African-American and Hispanic communities.' Or, one could add, the Orthodox Jewish community or the Staten Island community or the lacrosse community or ... fill in the blank." (Emphasis added)

All journalistic products are defined by the choices that preceded their creation, decisions driven by various capacities (time, money, amount of staff), skills (reporting, writing, education), needs (standing in a competitive - or non-competitive - market, desire for suburban readers, revenue) and personal interests of the decision-maker (all that messy subjectivity stuff).

Accepting and understanding these limitations frees journalists from a reactive agenda filled with event-oriented "news" and allows them to pursue a pro-active path toward those stories they deem - with the help of their readers - most interesting or most important.

Okrent continues:

"Here's another way of stating it: In a heterogeneous world, whose record is one newspaper even in the position to preserve? And what group of individuals, no matter how talented or dedicated, would dare arrogate to itself so godlike a role? … I mean no disrespect to The Times, but what discriminating citizen can really afford to rely on only one source of news? And can't all discriminating readers contextualize what their newspapers (or television stations or radio hosts or Web logs) tell them?" (Emphasis added)

Again, this is a liberating notion for newspapers. Because they can't be the "paper of record" and because news consumers are increasingly using multiple sources of information, newspapers can reform themselves into whatever content configuration best suits their community (and define that "community" for themselves.) For some, it will be providers of analysis, investigation and context; for others, the local appetite may crave more "chicken-dinner news"; for those with integrated online operations, both may be possible.

Finally, Okrent points out that the oft-used canard to describe newspapers - "the first draft of history" - is "definitionally imperfect, sometimes embarrassing and almost always needful of improvement."

As the author of this First Draft, I know that only too well.

Links

![]() New York Times: Daniel Okrent Paper of Record? No Way, No Reason, No Thanks

New York Times: Daniel Okrent Paper of Record? No Way, No Reason, No Thanks

April 23, 2004

USA Today Report: Dirty Laundry

In case you've been wondering why two top editors have lost their jobs at USA Today over the Jack Kelley scandal and why several more should, read the interal report written by Bill Hilliard, Bill Kovach and John Seigenthaler.

(It's here as web pages and here as a PDF).

I've excerpted some sections below on culture and communication as the underlying culprits that allowed Kelley's career of deception to flourish. As I was reading the report this morning, I was struck by the idea that, ironically, the disgraces of Kelley and Jayson Blair are ultimately going to be good for journalism. The forced soul-searching by the New York Times and USA Today - two of the country's three national newspapers - and the subsequent public laundering of their soiled dainties airs openly all the shortcomings of our profession and compels us to confront them.

Spurred also by work on newsroom dynamics by the Readership Institute, never before have newspaper journalists been so self-aware, which is the first step toward the change that is needed.

I've picked up the USA Today report past a lengthy opening section detailing Kelley's abuses and exploring the so-called "culture of fear" that kept his colleagues and managers from correcting them. Read on (all emphasis added):

"The effect of this culture, whatever it is called, combined with an organizational structure that creates walls between departments and reporting lines that divide management even in the same department, has been to silence the newsroom. In talking with reporters and editors, what we found absent from the newsroom at USA TODAY is the humming buzz of excited, disputing, energized reporters and editors.

"In the newsroom with the reputation for the most diverse staff in the country, there is little sign of an open exchange of experience and ideas. All those diverse voices too often seem silent. Top down, silence seems golden."This is not a culture that promotes the give-and-take that sharpens and

refines thought, the collegiality that magnifies the impact of resources, the

spirit that shares rewards and ameliorates distress, out of which great

journalism arises."(snip)

"For those editors who reject the idea that a fear factor muted and muzzled

criticisms that echoed around Jack Kelley's misdeeds, there should at least

be recognition that internal lines of communication at USA TODAY are

down and broken. Indeed they are."There are editors who say and believe that they have an "open-door"

policy, but in some areas of the newspaper their assertions are narrowly

shared with those who work under them. Even if the door is open and the

threshold is crossed, candor and sensitivity must mark the discussions that

ensue."We do not want to be misunderstood here. In finding a communications

disconnect we are not suggesting that a newsroom can be a debating

society, nor can it become a substitute for complaints that routinely are

handled by Human Resources. The very nature of reporting, writing and

editing the news involves raising and resolving, every day and in every

edition, differences of opinion over germane facts, or over style, or over the

play of stories. Tensions in this environment are inevitable. A newsroom

culture that cannot accommodate that sort of give-and-take mocks

standards of professionalism. That sort of give-and-take did not exist when

Kelley's reportage should have been subject to challenge."(snip)

"Current news executives are not alone responsible for this disconnect. Jack

Kelley thrived as a dishonest journalist for a dozen years. Every executive

who served during the years he betrayed readers shares USA TODAY's

embarrassment."The lines of communication now must be repaired by news managers who

understand that the newspaper is a human instrument, produced each day

by human beings of different talents, gifts and personalities."(snip)

"We acknowledge that our study of structure was inadequate to reach finite,

long-term conclusions. We are convinced, however, that whatever the

leadership problems that existed during Kelley's troubled time at the

newspaper, they were exacerbated by complex structural deficiencies that

dissipate authority and separate responsibility from accountability. Nothing

that we have observed has happened since to change that. A thoughtful reexamination

and logical streamlining of the corridors of authority, together

with a cogent reallocation of personnel, would serve to enhance

communication problems that are real. Persistent informed complaints

suggest that USA TODAY's organizational structure promotes a lack of

leadership, accountability and decision-making at the highest levels in the

newsroom."

More heads are certain to roll.

April 22, 2004

ASNE: Blogging the Ethics Panel

Jeff Jarvis is blogging the Ethics Panel at ASNE. Here's an excerpt:

Arthur Sulzberger of the New York Times: "We had a truly horrible year at the New York Times last year. ... "The scariest thing of all of last year for me... wasn't Jayson Blair.... The scariest part was that the people we lied about didn't bother to call because they just assumed that's the way newspapers worked. That's scary."

As Jeff says: "Amen and amen again." Read the rest.

A Fraud Flourishes in a Climate of Fear

Here's the lede on today's USA Today piece about the investigation into the Jack Kelley scandal:

"Lax editing and newsroom leadership, lack of staff communication, a star system, a workplace climate of fear and inconsistent rules on using anonymous sources helped former USA TODAY reporter Jack Kelley to fabricate and plagiarize stories for more than a decade, an independent panel of editors has concluded."

A team of newspaper analysts locked in a hotel room for a week with an endless supply of flip charts and magic markers couldn't have devised a more thorough diagnosis of the industry's ailments:

Lax editing: Lack of standards, or unwillingness to enforce them.

Newsroom leadership: Focused on process not product; looking inward, not outward.

Staff communications: Competition instead of collaboration; department silos worthy of the FBI and CIA.

Star system: Work only with the "easy" people; an inability, or unwillingness, to develop staff.

Climate of fear: Destructive, defensive culture bent on perfection not performance or risk.

Anonymous sources: Playing by their rules, not ours.

UPDATE: Hal Ritter, the managing editor for news of USA Today, also resigns because of the Kelley scandal.

Links

![]() The Hilliard/Kovach/Seigenthaler report on the scandal The problems of Jack Kelley and USA TODAY (also in PDF)

The Hilliard/Kovach/Seigenthaler report on the scandal The problems of Jack Kelley and USA TODAY (also in PDF)

New Readership Study: Culture Counts

A new study by the Readership Institute - released at the ASNE convention - focuses on attracting younger and more diverse readers to newspapers and on overcoming the internal cultural barriers that inhibit innovation.

A presentation (6 megs) by the institute to ASNE is rife with stark, direct language that declares "your newspaper is in peril" and warns that "your employees - and too many managers - still believe young adults will read newspaper more as they age."

The institute offers a three-part strategy:

Get into heads of your young and diverse readers.

Move from tweaking newspaper to continuous readership innovation.

Build organization with multi-year readership strategy that expects and rewards readership growth.

The study also creates a "Ready to Innovate" index that measures, among other things, newsroom culture and enumerates several employee-related characteristics that indicate a newspaper's willingness to take chances. Among them:

Their employees are much more "engaged" with the newspaper - that is, they are not only present for work and performing to standard, but often perform above standard and are deeply involved in helping the newspaper succeed in its goals.

They are better at articulating the mission and involving employees in decisions that affect them and the business.

They provide more training and development.

They have a higher proportion of female and non-white employees - and they are in positions of influence.

There's much more, including some classic change-resistant comments from a study of more than 6,600 newspaper employees -- "It's not my responsibility," for example - and interesting high-level points about how newspaper need to provide readers, especially younger readers, with positive readership experiences (such as the paper gives me "something to talk about" or it "makes me smarter") instead of negative ones (such as the newspapers "discriminates and stereotypes" or that it is "too much" to read).

Like all research, one conclusion doesn't fit all, but the Readership Institute is on the right track, examining not only potential reader behavior and current newsroom conditions, but how the latter influences the former.

They are a couple of slideshows up at the Readership Institute site. Read them. Have a positive experience.

Links

![]() Readership Institute In Their Own Words: How to Win Readers (Powerpoint 6 megs)

Readership Institute In Their Own Words: How to Win Readers (Powerpoint 6 megs)

![]() Readership Institute Background notes on the study

Readership Institute Background notes on the study

April 21, 2004

ASNE & Blogging: The Script Plays Out

UPDATE (04/21): Here's Jarvis' take on the panel:

"The good news about today's session on blogs with editors was that there was a session on blogs with editors. The room was full; they're curious; they know there's something happening here that's worth their attention. They're still not sure how to relate to blogs and what it means to their business. But there's something here." (Emphasis added)

EARTLIER POST: I've been waiting for Jeff Jarvis to post on ASNE's blogging panel today since he was on it, but he might have been so upset by Bush's speech (or was it the BMD -- burrito of mass destruction -- he ate aferward?) that he hasn't weighed in yet.

So, here's the convention newspaper's story on the panel, which summarizes thusly:

Citizen journalism argument, offered by J.D. Lasica: “The era of newspapers ‘breaking the news’ to most citizens is over – even in an online universe."Wary mainstream newspaper editor Tim Whyte, M.E. of The Signal in Santa Clarita, Calif., responds: “I think such efforts at ‘journalism,’ however, should be viewed with caution."

And so it goes.

ASNE's Diversity Study: Looking for Answers

Why do America's newspapers remain so white despite 25 years of effort to have them be more reflective of the communities they cover?

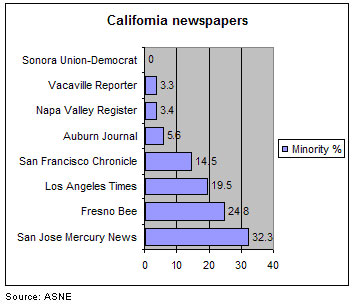

ASNE's annual hiring survey, released yesterday, reported that the percentage of minority newspaper journalists working in 2004 inched up 0.4 points to 12.95 percent - 100 people in absolute numbers. This can be seen as good news by  those who for whom any progress is better than none, but even they agree the overall number is woefully small. Worse, the bulk of minority journalists are concentrated in larger, urban papers, while many smaller newspapers remain lily white and even some larger papers in heavily minority communities lag the demographic changes happening around them. (See chart for examples).

those who for whom any progress is better than none, but even they agree the overall number is woefully small. Worse, the bulk of minority journalists are concentrated in larger, urban papers, while many smaller newspapers remain lily white and even some larger papers in heavily minority communities lag the demographic changes happening around them. (See chart for examples).

What is the problem? Is it a pipeline issue? In other words, are their insufficient minorities in journalism programs? Is it a pay issue? Are those minority journalism (and communications) students opting out of journalism at graduation for more lucrative starting positions in other industries? Is it a retention issue? Are minorities leaving then newspaper business faster than they can be hired?

Let's look at these three issues: The pipeline, attracting minority graduates to newspapers and retention.

The Pipeline

No one tracks journalism school enrollment and entry-level newspaper hiring more closely than Lee Becker, a professor at the University of Georgia's journalism school. Each year, Becker and his colleagues compile reports on who is attending journalism schools and how new journalism graduates are faring in the job market.

Becker said, in an article for the Freedom Forum, that it is "a myth that there are not enough minority applicants to alter the face of America's newsrooms." He told me yesterday in an interview: "There are more minority students looking for newspaper jobs than are able to get them. So, it's not simply a matter of an inadequate supply."

Becker said, in an article for the Freedom Forum, that it is "a myth that there are not enough minority applicants to alter the face of America's newsrooms." He told me yesterday in an interview: "There are more minority students looking for newspaper jobs than are able to get them. So, it's not simply a matter of an inadequate supply."

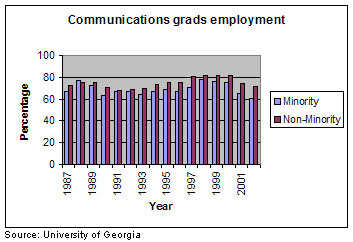

Newspapers reject some minority graduates, though, because they do not meet the criteria by which entry-level hires are judged, said Becker, and as a result white journalism school graduates continue to be hired at a higher rate than minority graduates, as they have for the 15 years Becker has tracked hiring. (See chart).

"Basically," he said, "if you can get the minority graduates to look just like the non-minority graduates in terms of some key things - their internship participation, their participation in the campus newspaper and their specialized socialization in news editorial journalism - they get hired at the same rate as non-minority students, not higher, at the same rate. The problem is minority students are more likely not to have those features, those characteristics than are the non-minority students. So, when the playing the field is leveled in that regard, the hiring appears to be color blind."

The uneven playing field derives in part from the characteristics of the universities many minority journalism students attend, said Becker.

Keith Woods, a Pointer Institute group leader who writes regularly on diversity issues, expanded on Becker's point.

Many minority students attend "historically black colleges, Indian universities or universities in the Southwest that serve principally Latinos," said Woods in an interview, "smaller programs, sometimes with weekly or monthly or no newspaper at all through which they can gather clips, and they're not getting the number of internships in those small programs that they need to be getting." (Asian journalism graduates, by comparison, "come into the industry come through the big programs in the country," Woods said.)

Woods recalled reading a column by Leonard Pitts, the Miami Herald writer who just won a Pulitzer for commentary, in which Pitts said he is "teaching journalism and running into kids who don't know what they need to know to do get themselves prepared for the daily journalism."

Becker said the newspaper industry doesn't tolerate young journalists who can't - to use a phrase I heard, and used, in many discussions about hiring when I worked at the San Francisco Examiner - "hit the ground running." Unfortunately, many minority journalism grads from smaller schools aren't able to do that, he said.

"Maybe they went to a university where the opportunities for them at the student daily weren't very great," said Becker, "or maybe they didn't feel welcome or maybe at that point in their careers they're weren't advised that that was important or maybe just made bad decisions. All of those are possible."

Of course, lack of preparation - by journalism school graduates of all colors - could be overcome with additional professional training, but that is not a component of the newsroom ethos.

"This is not an industry where there's a lot of investment in on-the-job training, particularly not for entry level people," Becker said. (Note: The newspaper industry invests only an equivalent of 0.7 percent of payroll in training, one-third what other U.S. industries spend.) "This is an industry where people are expected they day they walk in the newsroom to be able to do the job. … So, part of the obstacle is that not all of these students are up to that and so the industry can either address that or if it continues to uses those things as the screen I think it is going to make slow progress."

Becker pointed out that "many, many of the entry-level jobs are at very small newsrooms where if you have someone who you've hired that can't go out on the evening she or he was hired and cover a city council meeting, that's a big problem. … So, it's very hard for the industry to pass over someone who is able to do the job for someone who needs more investment, more training. The data suggests that's part of the issue."

Of course, the gap between newsroom expectation and academic preparation affects more than minority journalism graduates. Woods sees it a critical industry problem.

"Journalism education is an issue across the board," he said. "This is not a minority issue. Print journalism needs to communicate more strongly what it wants from the academy as we are getting lots of kids across the racial and ethnic spectrum that aren't ready. But, like everything else, when you cut by race and ethnicity it's going to hurt people of color more because they're in the minority to begin with and in many cases have greater needs. … The problem is at crisis level and I don't know that we're acting like it's at crisis level."

Attracting minority graduates to newspapers

Becker argued that the pipeline is swelling with available talent - 29 percent of all fall 2002 enrollees in journalism and mass communications programs were minorities, about half of them African American.

Of course - as Woods pointed out - many, if not most, do not intend to become newspaper journalists even though they may be studying some form of journalism in college.

"There may in fact be 29 percent minority enrollment in college journalism programs, but, like their white counterparts, a fairly small percentage of them are interested in print journalism," he said. "If you cut those numbers that way, you discover that the pipeline for journalists period, rather than folks who are going into public relations, for example, is at an alarmingly low number whether you're a person of color or whether you're white."

Both the industry and universities "need to get credible and meaningful numbers to compare on this issue so they can have a conversation that's more than just opinion," said Woods.

"You go into the classrooms any day of any week and you ask the students in there how many of them intend to be daily print journalists, you might be lucky to get a couple of hands to go up," he said. "And when you cut our numbers that way, then minority journalists will be severely slashed form the pool."

In his Freedom Forum paper, Becker reported numbers that show the newspaper industry is not doing a good job of recruiting even those minority graduates who are thinking about becoming print journalists.

"In 2001," he wrote, "only one in five of the minorities who sought a job with a daily newspaper - again to pick one example - actually took a job with a daily. Three in 10 took another media job. One in five took a job outside the field of communication. And one in five was unemployed six to eight months after graduation. Of those who actually got an offer, only half took the daily newspaper job."

The current newspaper job market is rotten for everybody (the number of employed newspaper journalists fell 500 positions to 54,200 in 2004, ASNE reported, continuing a nearly 20-year trend of more-or-less stagnation), but it's worse for freshly graduated minorities.

"The gap between the level of full-time employment of minority graduates and their counterparts increased to more than 10 percentage points," Becker reported in his latest survey (of 2002 graduates).

Indeed, minorities are not alone in being able to secure newspapers jobs - the same Becker survey found that "six to eight months after graduation, only half of the journalism and mass communication bachelor's degree recipients were working in the field of communication. The ratio has not been this low since 1992."

That kind of statistic sends a sobering, stay-away warning to any bright minority university student intent on finding a well-paying, rewarding career.

Retention

One area in the newspaper industry where parity exists between minorities and whites is retention - they both quit the business at the same rate, 5 percent (although there have been recent years, 2001 for example, in which more minorities left newsrooms than joined them).

However, as Woods pointed out, since hiring minorities is harder than hiring whites, when they leave the industry their departure has more of an impact.

"You got to consider that if the retention rate is exactly the same it is worse for people of color," he said. "In order for it to be equal, it would have to be proportionate. If you lose 10 percent of 100 and you lose 10 percent of 1,000, you have a different kind of a loss."

A study done in 2003 for ASNE found that "lack of professional challenge and limited opportunities" were the two primary reason minority journalists leave newspapers. Other findings offer a harbinger of a difficult future for efforts to diversify newsrooms:

Between "one-fifth and one-third" of minority journalists "do not expect to remain in journalism over the long term … a much stronger likelihood to leaving the field than white journalists.""The issue of advancement opportunities proved far more salient to journalists of color than to white journalists. For white journalists, the issue of advancement opportunities ranked last among the reason they might leave the field." (Emphasis added.)

Culture as a cause if minority journalist disenchantment

I have to wonder how much affect the defensive, destructive nature of most newsroom cultures has on attracting and keeping good minority journalists.

The Readership Institute's work examining newsroom culture finds that, on average, newspapers have workplace atmospheres that are unwelcoming to change, are disdainful of those who think differently than the norm and are intolerant of people who go against the grain. A minority reporter in a nearly all-white newsroom, one with a likely even whiter management structure, is by definition change, difference and not the norm.

As Woods pointed out, minorities quit newspapers for many of the same reasons as whites - lousy bosses, for example (the No. 1 reason most people quit their jobs) - but "there are other reasons, not necessarily different reasons, but maybe a broader spectrum of reasons" that apply to someone who looks, talks and thinks a bit differently than most other people in the newsroom.

Cultural change in newsrooms could go a long way to producing a change in color as well.

Links

![]() ASNE Newsroom employment drops again; diversity gains

ASNE Newsroom employment drops again; diversity gains

![]() ASNE Diversity in U.S. newspaper groups

ASNE Diversity in U.S. newspaper groups

April 20, 2004

Free Press: The Big Idea

Underneath the clutter of readership debates, circulation woes and lack of diversity, behind the baggage of tradition and monopoly, deep in the closet, past the rotting skeletons of Jayson Blair and Jack Kelley, there, in the corner, filmy with the dust of disregard is the Big Idea - a free press is necessary for a free people.

Amartya Sen, a Nobel economist, reminds us, in an essay for the World Association of Newspapers in advance of World Press Freedom Day (May 3), of four reasons why a free press is so important. They are:

Quality of life: "We have reason enough to want to communicate with each other and to understand better the world in which we live. … the suppression of people's ability to communicate with each other (has) the effect of directly reducing the quality of human life, even if the authoritarian country that imposes such suppression happens to be very rich in terms of gross national product (GNP)."Giving voice to the voiceless: "The rulers of a country are often insulated, in their own lives, from the misery of common people. They can live through a national calamity, such as a famine or some other disaster, without sharing the fate of the victims. If, however, they have to face public criticism in the media and to confront elections with an uncensored press, the rulers have to pay a price too, and this gives them a strong incentive to take timely action to avert such crises. It is, thus, not at all astonishing that no substantial famine has ever occurred in any independent country with a democratic form of government and a relatively free press."

Transfer of knowledge: The informational function of the press relates not only to … keeping people generally informed on what is going on where. … investigative journalism can unearth information that would have otherwise gone unnoticed or even unknown."

Formation of civic values: "Informed and unregimented formation of values requires openness of communication and argument. The freedom of the press is crucial to this process. Indeed, value formation is an interactive process, and the press has a major role in making these interactions possible. New standards and priorities (such as the norm of smaller families with less frequent child bearing, or greater recognition of the need for gender equity) emerge through public discourse, and it is public discussion, again, that spreads the new norms across different regions." (All emphasis added)

Sen's reasoning may seem self-evident to American journalists, who enjoy professional lives unfettered by interference from government and free from fear of death at the hands of those who disagree with what they write.

Despite successes by the current administration to suppress public information, the First Amendment and a host of shield laws continue to afford American journalists freedoms unheard of in so many other countries. This is why American journalists have an obligation to produce the highest quality journalism possible - as an example and an argument to journalists everywhere, and to those governments who would stifle them, that a free press is a fundamental component of a free society.

A lot of small thinking goes on in newspapers, much of devoted to the minutiae of the daily process. Let's not lose the Big Idea in the fog of petty concerns.

(Thanks to Tom Mangan for the tip.)

Links

![]() World Association of Newspapers: Amartya Sen What’s the Point of Press Freedom?

World Association of Newspapers: Amartya Sen What’s the Point of Press Freedom?

April 19, 2004

Applied Talent

Howell Raines writes in The Atlantic, describing the culture of the New York Times newsroom:

"For people who have worked at other newspapers, the biggest shock upon coming to the Times is that the level of talent is not higher than it is. Actually, it would be more accurate to say the level of applied talent. Very few unintelligent people get hired at the Times. So what's shocking to the newcomer is the amount of coasting."

Of course, Raines' Atlantic article is self-serving, but most autobiography is and simply because he portrays himself as a Yojimbo-like editorial samurai who, with his trusty sidekick Gerald Boyd, is intent on diverting the Times from its own inertia doesn't negate the ring of validity that echoes from some of his assertions. Remember, even the paranoid are right some of the time.

Even Jack Shafer, who portrays Raines as "bitter, conceited, and clueless," obliquely, albeit derisively, admits that Raines was probably right about slack level at the Times, but asserts that had Raines been a better manager he would have recognized that "coasting" is endemic in all large organizations and looked for answers that went beyond him being a solution of one. Writes Shafer:

"A sharper manager than Raines would have realized that what he was really observing was the Shafer Principle: 20 percent of employees do 80 percent of the work at almost every institution. Laud Raines for wanting to sack the featherbedders and deadwooders hiding behind Newspaper Guild skirts, but I'd wager that if you let Raines name his own, 20 percent of those employees would still do 80 percent of the work. It's an immutable law of the workplace." (Emphasis added)

And, therein lies the challenge facing most newspapers: Overcoming this institutional ennui and raising the level of applied talent, or, put another way, extracting the greatest possible amount of energy, intelligence and creativity from each journalist on the staff.

Within newsrooms one of the great obstacles to achieving this sort of personal fulfillment - and, hence, institutional fulfillment - is a defensive culture that discourages extra effort. The Times culture, he said, "actually consists of two distinct and parallel cultures, each fully cognizant of the other: the culture of achievement and the culture of complaint."

This observation holds for all newsrooms large and small, as we veterans of those places can attest, as does the cycle of what Raines characterizes as recruitment of new arrivals into these cultures by their standing members. Who hasn't seen a promising young reporter morph into a wizened, chronic griper after only a couple of years in the trenches?

The key challenge of newspaper managers is to encourage the culture of achievement and to provide an environment for journalists - at all stages of their careers - to grow professionally.

I have become increasingly convinced in the last few months, however - persuaded by interviews with dozens of editors, reporters and heads of journalism training organizations for a couple of projects I am involved in - that the greatest impediment news managers face to cultural change is themselves, especially middle managers, the desk editors, assignment editors and others with the most direct, day-to-day contact with the reporters and photographers.

A bright young reporter with two years experience told me recently that she is leaving journalism, heading off to law school, because she finds her editors so undemanding. Because she writes reasonably well, her stories sail through the desk and into the paper with nary a change while editors devote their energy to performing triage on more damaged copy. She is exactly the type of person - a graduate of a top five university, smart enough to get into one of the nation's best law schools - newspapers need to keep.

Another reporter, much more experienced and much more accomplished, with two decades in the business but still brimming with energy, told me much the same thing. He wants an editor to challenge him more, someone who does more than "flipping sentences," who will question the elements and direction of the story. For this type of critiquing, he turns to his peers, his fellow reporters.

One reporter described to me what he called "meeting reality," a world in which editors sell stories in news meetings based on budget lines they've written and then return to the newsroom to have the reporters "produce that story."

This is wrong. We know this. (And those anecdotes don't even include more actively destructive editors who view newsrooms as silos of fiefdoms over which they preside). It produces bad journalism and drives the best editors and reporters out of the business or into the deepest corners of the newsroom where they work with their heads down hoping not to be noticed - all of their talent unapplied.

I haven't written here for several weeks in part because I've been so busy, but also because this problem of bad management seems so large, so overwhelming, so systemically ingrained into the being of newsrooms that I had a difficult time envisioning a solution.

After all, if poor management is driving out the many of the best people (I'm waiting for ASNE to do a study of which type of people leave the business and where they go), what's left is a greater percentage of not-so-good people. Recently, a high-ranking editor of a large paper told me he was shocked by the depth of "mediocrity" in his newsroom and wondered if many staffers had the talent to do better journalism even if they had the inner motivation to do so.

This point is key when considering what type of training newsrooms should offer to improve the paper's journalism. It's not productive, for example, for a paper whose reporters struggle to report and write basic stories in a clear, declarative fashion - and whose desk editors don't have the skills or communications capacity to repair those stories - to send those reporters to a narrative writing seminar. Walk first, then run.

Complicating the matter further is the issue articulated by Raines - some people in many newsrooms (and in some newsrooms, many people) just don't work very hard. They are not, as my ruler-wielding, knuckle-rapping fifth-grade teacher Sister Mary Marguerite (now, she was an editor!), applying themselves.

Think about these things in a constructive manner for your own newsroom. What should your priority be: giving reporters and editors more skills or creating an environment that puts the greatest amount of skills to work? The former is a waste of time and training money without the latter.

Raines may have wrong about a lot of things, as his numerous critics have suggested - I'll leave that conclusion to those who know him and the Times better than I do - but he was right about this: Newspapers must change and change requires strong leadership, especially leadership where it counts in a newsroom, on the desk, by those editors whose numerous daily decisions not only shape the newspaper but the attitudes of the reporters they supervise.

"The day-to-day relationship with your editor is crucial, more important than" any type of training, one reporter told me. The solution needs to start there - with that editor.

Links

![]() The Atlantic: Howell Raines My Times

The Atlantic: Howell Raines My Times

![]() Slate: Jack Shafer The Autobiography of Howell Raines

Slate: Jack Shafer The Autobiography of Howell Raines