June 30, 2005

Debating the Future of Newspapers

A frothy conversation is bubbling through the online-news listserv about the New York Times weekender aoubt the Lawrence (Kan.) Journal-World, which the Times dubbed as the newspaper of the future for its multiple platforms, citizen participation and local, local news.

Read the story. It's a good starting point to think about changes any newspaper can make.

What I want to share, though, is part of an online-news comment made by Howard Owens, the new media director for the Ventura (Calif.) County Star, a pretty innovative paper in its own right. Here's what Owens said about newspapers and their role in community (all emphasis added):

If you're at a newspaper that has your community's name in the masthead, you are the glue that binds that community together. You are its hub and its spokes (to mix metaphors).Over the last thirty years or so, I think a lot of us in the newspaper business have forgotten our roots. We've struggled to become more objective, to be more professional, and sloughed off the chicken dinners and Eagle Scout promotions to interns, if they're covered at all. And as professionals, we've totally stigmatized covering such hyper-local news. No reporter wants to spend a Wednesday evening hearing about the Rotary scholarship winners. We all want to find out how the mayor is misappropriating cable franchise funds.

The whole argument that opening some of our news hole up to citizen journalism will dilute our brand or weaken our credibility is a bit paranoid. Being the voice of the people, and giving them voice, and helping to connect and bind our communities is part of our DNA and a prime part of our mission. It's how we can best serve our readers, our communities and our advertisers. It is our past, and it is our future. We simply have to do it.

Don't call it citizen journalism, if you object to that phrase. But figure out how to do it, how to manage it, how to make it core to who you are. If you don't, you have no future. Just like the publishers of the past, we have to learn to adapt the very definition of what we do to reach a bigger audience. It's the only way to survive, because if we don't do it, Craig Newmark, or Backfence, or some other entrepreneur will.

Let me repeat that: "Helping connect and bind our communities is part of our DNA and a prime part of our mission."

Don't reflect the community. Be the community.

June 29, 2005

The Audience is Talking Back

John Markoff's story in the Times today explaining the rise of user-created content on the Internet is rife with lessons for newspapers, especially those who still think the future of journalism lies in the practices of the past.

Here are a couple. Markoff writes:

"The new services offer a bottom-up creative process that is shifting the flow of information away from a one-way broadcast or publishing model, giving rise to a wave of new business ventures and touching off a scramble by media and technology companies to respond."

Lesson for newspapers:

Static media has lost every race for audience attention in the last half-century. Television stole time away from newspapers. The Internet steals time away from television. The interactive Net, one created and shared by users, will divert attention from the "broadcast" Net. To participate in this next layer of media, newspapers must become information resources rather than simply creators and journalists must become more transparent and connected to compete for credibility in a world of "we media."

Markoff writes:

"'We are now entering the participation age,' Jonathan I. Schwartz, the president and chief operating officer of Sun Microsystems, said on Monday at an industry conference in San Francisco. 'The really interesting thing about the network today is that individuals are starting to participate. The endpoints are starting to inform the center.'"

Lesson for newspapers:

Listen to the audience. They are telling you they want change. Remember the tag line you hear in movie theaters that use the THX sound system created by Lucasfilms? "The audience is listening." Now, the audience is talking back. Media that listen to, encourage and participate in that conversation will maintain relevance. Those that don't, will wither. [Read: Blogging the Beat.]

Markoff writes:

"Many Internet developers think that the Internet's new phase will shift power away from old-line media and software companies while rapidly bringing about an age of computerized 'augmentation' by blending the skills of tens of thousands of individuals."

Lesson for newspapers:

Use your platform, reach and resources to enable creation of a new "mass" made up of tens of thousands of "class." People want to participate in media - music, photography and, for newspapers, journalism. That doesn't mean we abandon the principles of journalism. It simply means we change the way we practice it, viewing the public not as a recipient, but as more of a partner.

Finally, a reminder for newspapers of the true power of the Internet - its connectivity. Here is a snip from the Pew Internet Project's 2005 report (PDF) on the state of the Internet:

"The internet is more than a bonding agent; it is also a bridging agent for creating and sustaining community. Some 84% of internet users, or close to 100 million people, belong to groups that have an online presence. More than half have joined those groups since getting internet access; those who were group members before getting access say their use of the internet has bound them closer to the group. Members of online groups also say the internet increases the chances that they will interact with people outside their social class, racial group or generational cohort."

To borrow a phrase from Hodding Carter and convert it into advice for newspapers: Don't reflect the community, be the community. [Read: Don't Reflect the Community, Be the Community.]

June 28, 2005

Dawning of the Age of the Journalist

Could it be that as the age of the journalism business wanes under the weight of an obsolete business model and changing audience that potential power of the individual journalist is on the rise? Are we entering the age of the journalist?

I think so.

What got me thinking about this was an article in the May 16 New Yorker (yeah, I'm way behind) that contrasted the sales of music CDs, which are flat, to the attendance at rock concerts, which has never been better. The magazine said:

"Consumers who seem reluctant to spend nineteen dollars for a CD apparently have few qualms about spending a hundred bucks or more to see a show."

Most rock and poartists today make their real money from touring, from being on the road, where they get to keep more than 50 percent of the gate receipts vs. the 12 cents a CD that may or may not come their way depending on whether the album's costs are ever recouped. As a result …

"… the fortunes of musicians and the fortunes of music labels have less and less to do with each other."

We are entering, says the New Yorker …

"… the first stage of what John Perry Barlow, a former lyricist for the Dead, called the shift from 'the music business' to the 'musician business.' In the musician business, the assets that once made the major labels so important - promotion, distribution, shelf space - matter less than the assets that belong to the artists, such as their ability to perform live. The value of songs falls, and the value of seeing an artist sing them rises, because the experience can't really be reproduced."

In this digital age, whose marvelous technology lowers the cost of music production and enables its universal distribution, thereby reducing both revenue and the cachet of exclusivity, the "experience" of seeing the music and of sharing that experience with others, trumps the music itself. "The old troubadour may have the most lucrative gig of all" in these times, says the New Yorker.

Apply this line of reasoning to journalism and it fits quite well.

The mechanisms of the journalism business - distribution, production, editorial hierarchy - face threatening economic, demographic and culture pressures.

The publishing exclusivity once claimed by the journalism business is lost to the technologically-enable democratization of the media.

The value of most forms of news produced by the journalism business is reduced to commodity levels.

What remains are the journalists. Increasingly, individual journalists, whether they work on their own or for news companies, are showing an ability to connect directly with their audiences, using the Internet to extend their reach far beyond their geographic base.

Certainly, the web enables columnists for the national newspapers like David Brooks and Paul Krugman of the Times or James Taranto of the Journal to spur national debate that spills far beyond the readership of their host papers. That is to be expected.

More surprising is the reach of regional columnists like Leonard Pitts of the Miami Herald or Dan Weintraub of the Sacramento Bee. During the California gubernatorial recall campaign that led we Californians being governed by Arnold Schwarzenegger, Weintraub often personified the Bee's coverage, attracting praise and criticism from both sides of the contest.

Some newspaper reporters who are now better known in some circles for their blogs than for their printed work. The other day, in a post about using blogs to extend a reporting beat, [Read: Blogging the Beat] I quoted Todd Bishop, who covers Microsoft for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and writes the Microsoft Blog, saying:

" … I was at an event where one employee introduced me to another as, "you know, that guy who writes the Microsoft blog for the P-I." That was an eye-opener for me, because it was pretty clear that they didn't know I wrote for the traditional newspaper, or didn't care."

Michael Bazeley, a tech writer for the San Jose Mercury News and author of Silicon Beat, said something similar:

"When I call people for stories or attend work-related events, many people know me now from the blog, not the paper."

Many people know Joshua Marshall better as the author of Talking Points Memo rather than the magazine journalist he was (and still is) before he began blogging. Other journalists, like Marc Cooper of the Nation, have followed Marshall's example.

And, of course, blogging itself and the still nascent emergence of forms of citizen journalism provide opportunities for individuals to straddle the worlds of journalism and advocacy in ways that create powerful connections between their unique points of view and their readers - a reader-to-publisher relationship that has for the most part dissolved between newspapers and their shrinking audiences.

Two years ago, I wrote:

"Quality sells. Relevance matters. The real lesson both the newsroom and the boardroom need to learn is that, in the age of the 24-hour scroll, the micro-fragmentation of electronic media, and the constant clamor for a news consumer's attention by everyone from the New York Times to yours truly, all that's left is the journalism." [ Read: There's Nothing Left but the Journalism.]

Today, I might amend that to read: "All that's left are the journalists."

Success in digital media - which newspapers are becoming whether they want to or not - requires differentiation.

If news is commodity, then in-depth reporting has value. If routine government coverage offers nothing but stenography, then interpretive reporting has value. If the conventions of traditional journalism produce bland and boring copy, then personality and point of view have value. If newspapers have become disconnected from community, then relationships between writer and reader have value.

What does this mean in the real world of news organizations? The creation of newsrooms in which the emphasis is on depth and context, in which journalists who are passionate and innovative are valued over those who are production-minded and defensive, and in which the principle role of managers is to create an environment that makes the first two things possible.

The future of news belongs to those who can connect to readers. That's something people do better than institutions.

Tags: Journalism, Newspapers, Media

June 26, 2005

Breslin on Reporting

Jimmmy Breslin spoke yesterday at the National Writers Workshop here in Fort Lauderdale, playing his best curmudgeon to the assembled crowd of reporters and writers.

I didn't take notes, but I can pass along a few anecdotes that show how little the principles of good reporting have changed in the many decades of Breslin's career -- and, sadly, how rarely they are practiced today.

Breslin told the story of his legendary interview with JFK's gravedigger. When Breslin arrived at the Capitol where the dead president's body was laid out, he saw a mass of what called "3,000 reporters." I thought, said Breslin, if I stay here I'm going get a story like 3,000 other reporters and get paid like 3,000 other reporters.

So, Breslin left the Capitol and made his way alone to Arlington Natioinal Cemetery -- after all, he said, it was just "a story about a dead body" -- where he found the man who dug JFK's grave.

The resulting column is considered by some to be the definitive piece of reporting on the assassination.

The lesson, of course, is obvious: The best journalism comes from independent thinking.

There were many young journalists in the room and several asked Breslin for advice on how to be a good reporter. His best response: You've got two feet. Use them. In other words, get off the phone, out of the office and connect with real people.

Good advice for the 1960s. Good advice now.

June 25, 2005

Blogging the Beat

I am in Fort Lauderdale where I have been working this week with the Sun-Sentinel on the Tomorrow's Workforce project (hence, the blogging break), but today I am doing a quick session at the National Writers Workshop on blogging for reporters.

I am in Fort Lauderdale where I have been working this week with the Sun-Sentinel on the Tomorrow's Workforce project (hence, the blogging break), but today I am doing a quick session at the National Writers Workshop on blogging for reporters.

To prepare, I talked with several reporters who write blogs. Here's what they had to say about the advantages blogging brings to a beat reporter.

Gery Woelfel, The Woelfel World of Sports, Racine Journal Times:

"While I've been a journalist for almost three decades now, and still firmly believe in the traditional journalistic standards, I think it's imperative we present our news outside the box. Most of our young readers have been exposed to things we never were at their age. … I always get a chuckle out of fellow journalists, mostly newcomers to the profession, that blogs are the future of journalism. I beg to disagree; I think they're the 'present' of journalism.

Michael Bazeley, Silicon Beat, San Jose Mercury News:

"I think blogging has also sharpened my reporting some. Because Matt and I put original content that comes from original reporting on the blog, we are spending more time mining our beats, talking to sources and reading about issues. We're consuming more information, which can only be good."

Todd Bishop, Microsoft Blog, Seattle Post-Intelligencer:

"… it's pretty clear that having the weblog has increased the general awareness of the paper's Microsoft coverage among our readers and also among Microsoft employees. Some number of months after starting the blog, I was at an event where one employee introduced me to another as, "you know, that guy who writes the Microsoft blog for the P-I." That was an eye-opener for me, because it was pretty clear that they didn't know I wrote for the traditional newspaper, or didn't care."

Matt Williams, Inside Scoop, Greensboro News-Record:

"Does it help my reporting? Yes. It does take some time to blog, but it saves me from writing a whole story about some marginally important item that I might have felt necessary if I didn't have another outlet. That gives me more time for in-depth stories that make it into the paper."

There's plenty more in the presentation. If you can stand another set of Powerpoint slides, go get them here.

I should be back to my regular blogging next week.

June 16, 2005

Extra! Extra!

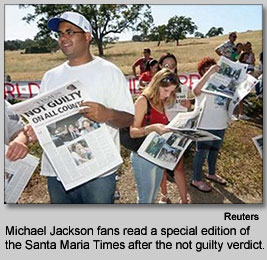

When do newspapers still have the edge on breaking news? When you're standing in a field without a TV set or a web connection - at least if that field is located in the middle of Central California near Michael Jackson's so-called ranch.

When do newspapers still have the edge on breaking news? When you're standing in a field without a TV set or a web connection - at least if that field is located in the middle of Central California near Michael Jackson's so-called ranch.

Most people who cared, and many more who didn't, heard about the not guilty verdict in the Jackson molestation case from TV (such as these folks in Times Square) or the web (from pages like these on Yahoo). A few, though, bought special editions of the Santa Maria Times, which put a $1.00 commemorative edition of the paper post-verdict and also welcomed in an editorial the end of the local community's 15 minutes of fame.

What struck me about the this picture is how anachronistic it is. The image of people absorbed in freshly-printed, breaking news is belongs to an era that has long since passed. It is reminiscent of photos like this one from the end of World War II or of this front page reporting on D-Day.

This image taken the other day in Times Square is more typical of today's world - media that changes moment by moment, memorable for seconds as it passes through our lives or we pass it its.

I'm glad the Santa Maria Times put out an Extra!. It is as much an artifact as Jackson himself.

June 15, 2005

Tech Troubles from Hell

As you may have noticed, I have been mostly off-line since Sunday -- all because my hosting company (ValueWeb) did a server migration to cut down on comment spam and scrambled just about everything. I've got email back and some of the site, but the cgi scripts needed to run the blog still aren't working. I'm looking for the silver lining, but ain't seen it yet. I'm uploading this by hand.

Can we all say this together: Isn't it about time -- 10+ years into the web -- that we arrived a some kind of shared standard? Arrrrgh!

Stay tuned. Cheers ...

Tim

June 10, 2005

Here's to You, Cliché Writers Everywhere

The death of actress Ann Anne Bancroft this week produced a gaggle of "Mrs. Robinson" headlines - and the subsequent send-up of same by sharp-eyed (and sharp-tongued) headline watchers.

They rightly skewer the "Here's to You" heds as predictable clichés. I'll go one step further (and this is not about copy editors vs. reporters, so back in your seats, kids): Clichés are the bane of good writing and their ubiquitous presence in newspapers directly undercuts efforts to reach younger readers, who prefer "surprise and humor." [Read: The Readership Institute's work in at the Minneapolis Star-Tribune and Readership: Survival Lessons for the Future from Minneapolis.]

Brian Montopoli of CJR Daily slices and dices the Bancroft heds most deftly in this piece, "Hard Day on the Rim." He writes:

"There's gotta be something in the song, you think -- go back to the song. You get up from your cube, stare out the window. Start singing to yourself. Wait -- shit -- that's it! The chorus! It's so obvious! There's that part where Simon and Garfunkel croon, "Here's to you, Mrs. Robinson." Why not just that? Here's to you, Mrs. Robinson. It's so simple, but it says everything. Everything. You type in the headline, sit back, and rub your eyes. You're smiling, for the first time in days." (Emphasis added.)

Nicole Stockdale, a copy editor, rounds up a collection of Mrs. Robinsons heds on her blog, A Capital Idea, and points to Bill Walsh, who links to a good (and only mildly defensive discussion) of the hed on Testy Copy Editors. Tom Mangan, a copy editor at the San Jose Mercury news who blogs here, offers the best reason to avoid clichés:

"The test for stories like this is: Does something jump immediately to mind?"If so, whatever jumps immediately to mind must be rejected on the grounds that everybody else will have the same idea. Now, if you learn of Ms. Bancroft's death six minutes before deadline and there's no time for something better, then, sure, go with the first instinct. But if you're not that pressed for time, press yourself for something better.

"The big however: With obits, respect for the dead must figure in the equation, which is why the grownups at the better papers played it straight w/Ms. Bancroft's passing." (Emphasis added.)

Tom also is the keeper of Banned for Life, a handy list of clichés to avoid (or employ, I suppose, if you're so inclined.) A few from the list:

Campaign trail: What on this green earth is a campaign trail? (Besides journalistic nonsense, of course)

XXX years young: This hackneyed "inspirational" phrase is used on any old person who isn't dying right in front of the reporter.

(ACES, the copy editors association, also keeps lists of hackneyed ledes and worn out phrases. Read them, learn them, laugh at them and avoid them.)

Cliched ledes and heds abound in newspapers and are easy to find. Here is a collection of "but" ledes I put together in a few minutes of web searching. Let's do a few searches of Google news and see how often some of the no-no phrases compiled by Mimi Burkhardt for ACES show up:

Carnival atmosphere: 14 pages of returns, including this lede, "Despite the rain, a carnival atmosphere permeated throughout the downtown …"

Heated debate: 35 pages of returns, including this hed, "Patriot Act gets heated debate," over this lede, "Debate over the Patriot Act heated up Tuesday …"

Manicured lawns: 11 pages of returns, including this lede: "They lived in a Sharpsville mansion ringed by manicured lawns …"

You get the idea. Despite most writers and editors knowing that tired writing equals tired reading, they continue to over-season newspaper copy with clichés - a recipe for blandness.

I often write about issues and forces in the newspaper industry that journalists cannot control - the changing demographics and economics of the business, for example - but what words appear in the paper are their choice.

Fresh writing is a good place for change to begin.

Tags: Journalism, Newspapers, Media

June 07, 2005

Working at Change: How One Newspaper Created a New ‘Compact’ with Readers

As I noted the other day when I wrote about John Robinson’s efforts to make his newspaper in Greensboro more local, change is hard work – and at a newspaper it can be dauntingly so.

Not only must a newspaper bent on innovation overcome the cultural obstacles and the journalistic traditions of what is considered news and the so-called proper presentation of it, it must also confront and resolve a myriad of production, advertising and logistical issues.

Not only must a newspaper bent on innovation overcome the cultural obstacles and the journalistic traditions of what is considered news and the so-called proper presentation of it, it must also confront and resolve a myriad of production, advertising and logistical issues.

John Kirkpatrick, a former colleague of mine who is now the editor and publisher

of the Patriot-News in Harrisburg, Pa., recently sent me a copy of the new tabloid (i.e., compact) version of his paper. Aptly, it bears a shorter name: The Patriot.

The Patriot-News and its more diminutive offspring co-exist, two editions produced by the same newsroom, pressroom and sales force, a first says Kirkpatrick. (The notion of two versions of the same paper, rather than, say, converting the broadsheet into a tab, was inspired by this Malcolm Gladwell story in the New Yorker by about ketchup headlined: “The Ketchup Conundrum: Mustard now comes in dozens of varieties. Why has ketchup stayed the same?”) The goal of the Patriot was to produce a different product for readers – mostly younger people and women – who wanted a quicker, but still intelligent package of news.

“The one-size-fits-all model is no longer ideal for newspapers in today's marketplace any more than it is ideal for magazines or cars or spaghetti sauce,” Kirkpatrick said in an email to me. “…We decided to give readers the kind of choice in their daily paper that they have everywhere else, to answer the ‘broadsheet or tab’ debate by producing both.”

I had asked Kirkpatrick to elaborate on how the Patriot came into being with the intent of pulling out lessons for other journalists. He responded at length (paraphrasing Mark Twain: “My goal was to write something shorter. I didn't have time.”)

I’m going to run Kirkpatrick’s complete letter, which you should read because he walks us through all the decisions, philosophical, physical and financial, that had to be made to product the Patriot. First, though, I’ll give his shortcut version and a few excerpts from the longer letter. Here’s the quick read.

“So, how did we do it?

It was easy.

We came up with an idea.

We ignored the common sense which called it impossible.

We ran smack into a million operational issues that seemed intractable.

We met as a paper and decided to suspend all sense of limitation.

We solved every problem.

We practiced a few times.

Then we produced The Patriot.”

Here are some excerpts, with my headings and comments:

The Biggest Lessons: “It turns out that ‘Just because it’s been done this way doesn’t mean we can’t do it differently’ can be a powerful message. It turns out that going to the folks on the front lines, presenting all the available information and being willing to answer any question -- no matter how painful -- is a powerful tool. It turns out that when you ask each and every staff member to make this ‘his or her; project and to take a leadership role, it actually works. It turns out that taking advantage of, rather than working around, the interdependence of departments not only solves problems but it creates opportunities. It turns out that when you put your trust the staff, they do amazing things.”

There is so much to learn from the making of the Patriot, but the above paragraph contains the most important lesson because it addresses directly the culture issue: Communication from management, transparency of information and decision-making, empowerment of the front line results in engagement, creativity and innovation.

What Readers Want: “This group of readers is overwhelmingly NOT interested in a dumbed down ‘youth publication.’ In fact, they are resistant and even resentful of one. They don't want fluff. They want real news, especially local news, in a condensed form. … They wanted a paper infused with our values -- the integrity of the news columns, the integrity of our advertising, our commitment to the community -- but not confined by the past.”

This fits in with what the Readership Institute found in its study (PDF) of reader experiences: Readers are drawn to publications that respect their intelligence and make them smarter.

Communication Trumps Adversity: “Not having someone else to copy, having to figure this out for ourselves, proved to be the best part of the experience. We had to listen to the readers and we had to work together as an entire newspaper. We thought we did both of those things in the past, but this pushed us much farther than we ever imagined. … We had leaders and managers at all levels who were willing to be bold, to question assumptions, to look past roadblocks and ask “what if?” And folks throughout the paper embraced one underlying idea: it was better to forge our own future than bemoan our fate.

What if? That question holds the power to change. Newspapers may or may not be dying. That debate continues (Farhi vs. Meyer). What is certain, though, is that the future of the news game will be played on an entirely different field that those we have today. We best get ready for it. [Read: The Mood of the Newsroom for a series of “what if” questions.]

Below is Kirkpatrick’s full letter. Read it. I’ve added all the bold-face emphasis and the indenting:

How the Patriot-News Made the Patriot

John Kirkpatrick, Editor and Publisher, June 3, 2005

Over the past few years, we’ve done things in every part of our operation to drive readership and to develop stronger relationships with our advertisers. We believed that quality would be the engine that drove our growth.

By many measures, we were succeeding. In 2004, The Patriot-News was named one of the top 50 papers in the world for color reproduction; we won an industry award as the top large paper in the state; we were second in Pennsylvania Newspaper of the Year; and took top honors for our promotion work. We turned our daily sports section into a tab. We redesigned and expanded our zoned weekly sections, rebranding them as “your community newspaper” within the broadsheet. We offered frequent info boxes and update boxes with stories; expanded our coverage of ordinary people; added more in-paper promos of today’s and upcoming content. We added glossy niche magazines, started a daily e-mail news update (Know@Noon) and expanded our community efforts. Editor & Publisher named us as one of their annual “10 That Do It Right.”

By many measures, we were succeeding. In 2004, The Patriot-News was named one of the top 50 papers in the world for color reproduction; we won an industry award as the top large paper in the state; we were second in Pennsylvania Newspaper of the Year; and took top honors for our promotion work. We turned our daily sports section into a tab. We redesigned and expanded our zoned weekly sections, rebranding them as “your community newspaper” within the broadsheet. We offered frequent info boxes and update boxes with stories; expanded our coverage of ordinary people; added more in-paper promos of today’s and upcoming content. We added glossy niche magazines, started a daily e-mail news update (Know@Noon) and expanded our community efforts. Editor & Publisher named us as one of their annual “10 That Do It Right.”

Yet with all this innovation -- and success -- we were struggling simply to maintain relatively flat circulation. Even though our numbers were better than most papers (we were up 1,183 in the last Fas-Fax), we were not growing the way we felt we needed or wanted to. More ominously, we faced a growing divide between the way our traditional readers want information and the way time-starved readers want it.

The circulation trend line meant that, over time, our paper would be forced to cut back rather than grow. That wasn't the future we wanted. And growing circulation through discounting and non strategic third party sales was no answer.

When we looked at the numbers, it was clear that (in our slow-growth market) the greatest opportunity was getting time-starved occasional readers -- many of them younger and women -- to read us more often. But we have found that “updating” the paper to attract them alienates some of our core readers while not attracting new readers at the same rate. It seemed like a lose-lose proposition.

When we converted our Sports section to a tab, we did attract new readers -- especially women and casual sports fans -- to the section. This allowed us to sell advertising into the section that we never had before. Yet we weathered numerous and ongoing complaints from loyal broadsheet fans.

Our conclusion: The one-size-fits-all model is no longer ideal for newspapers in today's marketplace any more than it is ideal for magazines or cars or spaghetti sauce. You can now buy 10 different version of a Hershey's Kiss but only version of the daily newspaper. We decided to give readers the kind of choice in their daily paper that they have everywhere else, to answer the “broadsheet or tab” debate by producing both.

Because we were the first paper in the United States to head down this path, we had to work through hundreds of thorny operational issues as well as test our ideas in the market. Not having someone else to copy, having to figure this out for ourselves, proved to be the best part of the experience. We had to listen to the readers and we had to work together as an entire newspaper. We thought we did both of those things in the past, but this pushed us much farther than we ever imagined.

Nearly everything changed between our first prototype covers and what is on the street right now -- the name, the design, the editorial focus, how we were going to sell, how we would print it, and much more. What didn't change was hearing from time-starved and occasional readers that they would value a compact version of The Patriot-News. They wanted a paper infused with our values -- the integrity of the news columns, the integrity of our advertising, our commitment to the community -- but not confined by the past.

Here are some of the key things we discovered from focus groups and other feedback:

1. This group of readers is overwhelmingly NOT interested in a dumbed down “youth publication.'” In fact, they are resistant and even resentful of one. They don't want fluff. They want real news, especially local news, in a condensed form. Thus this product is editorially driven –which is not only a matter of integrity, it’s what we do best.2. These busy readers were clear that they would not go out of their way to get the paper. We were planning on single copy only, sold in normal outlets as well as places like health clubs. Instead, they told us over and over that we almost had to place it in their hands. We had been planning to print this at the end of the press run and have a small, additional group of distributors get it out on the street (much work had been done in this regard). We switched to printing it in the middle of the press run, allowing for home delivery along with the broadsheet. At first, we didn't understand how important it is to have the newspaper where these time-starved readers are, when they are there. It is our job to make that connection.

3. Advertising needs to be proportional to the news. If it is, it will have great impact. That means getting second ads for the compact, devising complex conversion charts, and much more. It is a huge undertaking. The easy way out would have been simply to reduce an ad until it fits, but we didn't think that would work long term. On the other hand, while both local and national advertisers have had lots of questions, nearly all have been behind the idea of growing full paid circulation with the compact edition. They were hungry for us to try something new, especially if it skewed to time-starved women.

4. Marketing gurus do not get excited by simple, literal ad campaigns but this type of promotion is essential. Our ad agency’s first clever and inventive ideas fell flat. Clarity and simplicity were what resonated with potential readers.

5. Doing this while you are strong, with a strong brand, really helps. We heard over and over that people liked us but simply didn't have time to read the broadsheet. Getting the news in a convenient format from us was far more valuable to these readers than we had imagined.

When people ask us “how did you do it?” often what they mean is: how do we manage the logistics of producing two formats on deadline, five days a week? To make things even more challenging, since we didn't know if it would succeed, we tried to do as much as possible with existing resources. Here were some keys:

1. To create time on the press, we collapsed two daily zoned editions (Lebanon and Carlisle) into our final edition. We added two additional pages to Final to accommodate the Lebanon/Carlisle stories, and redesigned our Local/State section to highlight the news from each region. This was a painful move. Our bureaus had worked hard to make these editions competitive with small dailies in Lebanon and Carlisle. We were all concerned. We had heavy financial and emotional ties to those editions. The newsroom made numerous other changes for the compact related to workflow, schedules, news meetings and more. But the zones were the most visible to readers and advertisers.2. The advertising side of this is extremely complicated. At one point, the folks trying to work all the details said they should meet on the roof so it would be easier if they decided to jump. In the end, it has meant the likelihood of scrapping our present rate card and redoing it in a very different way. That project is almost as big as launching the tab.

3. We were spending a great deal of money on a smaller and smaller telemarketing pool as well as other ways of getting new broadsheet subscribers. We decided to move that money to the new project. That was a big gamble for circulation. Our goal is not to migrate readers or undo the broadsheet; it is to expand the market. But we felt the long term potential was much greater on the compact side. Then, working with hundreds of independent agents, more than 400 single copy outlets, introducing address-specific home delivery, and keeping the broadsheet moving forward was no easy task.

4. IT needed to make sure page pairing and all our systems worked for this project. That meant putting other projects on hold.

5. To save money and make this work, we run our State edition broadsheet in a straight mode. Then we run the compact in a collect mode. We then run Final in a straight mode again, keeping our Final off time the same. It is also a challenge managing the compact’s newshole in 8-page increments (necessary because we run collect) -- we want enough space to be a valuable news source, not so much that we use filler and defeat the purpose of giving busy readers a tight edit.

6. To give us additional money for the compact, we put off non-operational expenses that we had planned.

In the end, our ability to solve myriad problems came down to one thing: the whole paper coming together. There were a ton of staff meetings and constant communication. We held a paper-wide meeting (our first ever) to make the case for this project. We had leaders and managers at all levels who were willing to be bold, to question assumptions, to look past roadblocks and ask “what if?” And folks throughout the paper embraced one underlying idea: it was better to forge our own future than bemoan our fate.

It turns out that “Just because it’s been done this way doesn’t mean we can’t do it differently” can be a powerful message. It turns out that going to the folks on the front lines, presenting all the available information and being willing to answer any question -- no matter how painful -- is a powerful tool. It turns out that when you ask each and every staff member to make this “his or her” project and to take a leadership role, it actually works. It turns out that taking advantage of, rather than working around, the interdependence of departments not only solves problems but it creates opportunities. It turns out that when you put your trust the staff, they do amazing things.

Everything, of course, isn’t perfect. There were those who refused to engage. There are still those on the sidelines. But they are few and far between.

And in the end, we did it.

Now, of course, we'll see what the consumers have to say. When all is said and done, that is what really counts.

June 03, 2005

Oh, Canada: An Innovation Presentation

I spoke yesterday at Canadian Newspaper Association's annual conference, held this year in Ottawa. I pulled together a number of the ideas you've seen on First Draft for a presentation on newsroom innovation.

Here's some highlights from the talk. The full set of slides are here.

I spoke about risk averse nature of newspapers as organizations, and their continued hesitancy about investing in the future. Two quotes were salient, the first from 11 years ago:

"Newspapers have made almost every kind of radical move except transforming themselves. It's as if they've considered every possible option but the most urgent - change. … That makes newspapers the biggest and saddest losers in the information revolution." -- Jon Katz, Wired magazine, 09/1994.

… and the second from this year:

"Despite the new demands, there is more evidence than ever that the mainstream media are investing only cautiously in building new audiences." -- State of the News Media, 2005, Project for Excellence in Journalism.

I presented two broad themes for change, Intentional Journalism and Explode the Newsroom. Here are their key points:

The idea of Intentional Journalism develops from asking these questions:

Someone gives you your current annual newsroom budget and says: Make any kind of news operation you want. Would you make the same newspaper? Would you create the same beats, departments, production and decision-making processes? Would you hire the same people? Would you design the paper and its web site in the same formats?

Of course you wouldn't. So these steps are starting points for change:

Develop a strategic plan: What are your readership goals for 5 years? 10 years?

Develop annual newsroom objectives: Specific, strategic and unique to your community.

Develop annual individual objectives: Not evaluations, but personal learning plans for every staffer from the admin to exec editor; what you should be able to do a year from now that you can't do now.

Build learning time into the budget: Newsroom training budgets are important, but even more critical is learning time; allocate it on an FTE basis.

Evaluate -- How are we doing?: The No. 1 question of the day, every day. What is working? What is not? Are we making progress toward our larger goals?

Challenge assumptions: Why do we do things this way? Change cannot happen without questioning the status quo.

Explode the Newsroom is based on the premise that small measures are no longer sufficient to change the industry, so we must rethink, refocus an reinvent, using these concepts as starting points:

Don't Tinker, Explode: Big rewards come from big bets.

The 10% Solution: Devote 10 percent of the newsroom budget each year to product and staff development.

Structure by Horizontally, Not Vertically: Tear down the Sports, News, Features and Business silos; reconstitute around virtual communities.

Go Weekly -- Every Day: Mass is dead; class matters.

Be the Tip of the Information Iceberg: Reverse the print-online priority equation; the newspaper must become the gateway to information, not the destination.

Lead from the Middle, Not the Top: You cannot lead from behind the desk; Get the editors out of the offices and onto the newsroom floor.

Don't Cover the Community, Be the Community: Empower readers, enable citizen journalism; get engaged; lead civic discourse; be people-centric.

If you'd like to read the original First Draft posts on these topics, they are:

![]() Read: Explode the Newsroom: Six Ways to Rebuild the System.

Read: Explode the Newsroom: Six Ways to Rebuild the System.

![]() Read: ASNE Convention: Six Things that Should be on the Agenda.

Read: ASNE Convention: Six Things that Should be on the Agenda.

![]() Read: Read: New Values for a New Age of Journalism..

Read: Read: New Values for a New Age of Journalism..

![]() Read: Intentional Journalism.

Read: Intentional Journalism.

Tags: Journalism, Newspapers, Media

June 01, 2005

The $34,000 Question: What Will You Give Up to Get More Local?

Change comes with a price. The more radical the shift, the higher the cost. For newspapers, the tariff to a different future must be the sacrifice of sacred cows, damage to some newsroom egos and even the loss of some of today's readers in the hopes of securing more of tomorrow's.

At the Greensboro (N.C.) News-Record, the price was $34,000, the amount the paper paid annually for the New York Times news service. Editor John Robinson traded in the Times so he could pay for more local news coverage. In that decision is the microcosm of the value equation every change-minded newspaper editor in America must face: What do I give up in order to get something new?

Robinson announced the end of the Times service in a column and on his blog. He wrote:

"I made the decision, and I admit that I hate it."We aren't doing this because of that newspaper's recent ethical lapses or because it is a lightning rod for readers who see political bias in the news coverage.

"In fact, I put off the decision to cancel as long as I reasonably could. The Times produces some of the world's best journalism, and I want our readers to have access to it. But given our direction in focusing on local news, we could certainly devote the $34,000 a year we spend on the Times reports better elsewhere." (Emphasis added.)

Robinson is a leader in efforts to change newspapers for the better. He blogs, he communicates with readers, he is rebuilding the News-Record around the reader experiences identified by the Readership Institute. See here and here for additional posts by Robinson on the Times decision and on reaction from his readers.

Newsroom managers are, of course, accustomed to balancing budgets and juggling money, but what is at stake in Robinson's decision is not money, but rather the definition of what a local newspaper should be.

Under the traditional, full-service model of newspaper, all but the smallest dailies publish front pages that are a mix of the top national and international news (as determined by the AP or the syndicate wires) and staff-written local news. Editors stuff the front sections of these papers, as well as the most of the feature, business and sport sections, with mostly wire stories drawn from news budgets heavy with stories about government, economic indicators and pro and college sports.

The result is a journalistic generica, a compendium of soporific sameness the blurs the distinction of one newspaper from another. In this environment, local news is the only differentiator, the only reason for someone to buy (or read online) the Daily Blatt instead of the New York Times.

In last two decades, two forces combined to accelerate the homogenization of newspapers.

First, luxury news got cheaper. When I edited a now-defunct, 45,000 Richmond (Calif.) Independent in the early 1980s, I leaped at the opportunity when the Times and the Washington Post made their news services available to smaller papers. Foolishly, I paid the thousands per year for this name-brand news because I thought it gave the paper more cachet than an "ordinary" AP or UPI story. Also, like in Greensboro, the editorial page editor wanted the Times columnists. (Some years later, with the paper rasping in its death throes, the victim of a competitor who followed the growth to the suburbs first, I was forced to cancel the Times contract, by then renegotiated downward several times, to save a few dollars more.)

I was not alone, though, in the '80s, Times and Post bylines sprouted for the first times from the front pages of local newspapers across the country, and editors of those papers came to rely on the daily news budgets to determine play for national and international stories.

Second, newspapering became less of a craft and more of a profession. The waves of freshly graduated reporters who emerged from the nation's growing number of journalism schools in the last 20 years had ambitions that exceeded covering the local city council or prep sports or community theater. If they couldn't land a job on the Times or the Post, they brought the expectations of those papers to their local newspapers.

One the one hand, this was a good thing. Higher expectations produced better more enterprising reporting, higher writing standards and better local journalism overall. The flip side, though, was the loss of distinctive community reporting. Why cover local theater when Broadway beckoned? Why not assign (several) staff writers (and a sports columnist) to nearby pro teams? Why not have a business columnist who writes about national issues? Why not open a Washington bureau? Why not review movies or books with staff writers?

All fine and good, perhaps, but the cumulative result was an increasing number of resources -- both bodies and budget - devoted to staff-written news that replicated what the wires were already doing and for which the paper was already paying. This was not a good use of resources - paying twice (or more if you consider that many newspapers pay multiple times for the AP, Reuters, the Times, the Post, and maybe their chain's news service) for something and then throwing most of it away. These are bodies and budget aree not devoted to the one information commodity that currently (but not forever) separates newspapers from their competitors: Local news.

Jeff Jarvis pulled on a similar thread the other day when he wrote (all emphasis added):

"Does every newspaper across the country need its own movie critic? The movies are the same coast-to-coast. The information we need to decide whether to go is the same. So why not plop in Roger Ebert? Or why not plop in reviews by your funny neighbor who knows the good stuff?"Ditto sports columnists. Ditto political columnists. Get rid of the voices on high and get more voices from down on the ground and you'll improve the conversation and save money.

"Death to commodified news: As an industry, we waste a fortune manhandling the same commodified news everybody already knows. But it's more than just a waste; it drags us down into an oppressive sameness. We all got overdosed on Schaivovision and Popevision and Bridevision. … Breaking away from the pack is extremely difficult and risky, but every news outlet needs to have a unique voice and value or it will get lost in a crowd.

"Similarly, newspapers and their audiences would be best served concentrating on what they do best: local, local, local. If they gave us the local news that no one else could gather and report, they'd be worth more to us. But this, too, is a hard habit to break: not sending the 15,001st correspondent to the political conventions, not editing the already edited AP report, not printing the stock tables."

In other words, precisely during a time when other media were differentiating, when the expansion of news media and transference of publishing power from the few to the many made distinction of voice even more critical, newspapers were becoming less unique and more generic.

This brings us back to John Robinson. I asked him to elaborate on the thinking that went into his decision to trade in the Times for more local. His comments follow, with some additional thoughts by me. I've also added specific questions where originally they were much broader.

Would you lose or gain readers with an all-local front page?

Robinson: "We believe that local is the way to go. Our front page now is routinely all local, except on Mondays, when there's not much live news that happened on Sunday and we run a bit out of steam. Our research indicates that readers don't rely on us for national and international news. What we do publish is often on the national networks at 6:30 p.m. the night before so what value are we providing our readers by printing it on the front page 12 hours later?"

Robinson's question should be inscribed on the keyboard or lens cap of every journalist in America: "What value are we providing our readers?" This question cuts to the heart of the newsroom value system, the hierarchy of importance that drives every daily news decision. Competition, Authority, Individualism - these are today's newsroom values and for the most part they reflect a desire by journalists to win approval of their peers, to be good journalists. A question like Robinson's reframes journalism to reflect the values of the community, to, by contrast, be a good citizen. What might help readers? Context, Collaboration, Interaction for starters. [Read: New Values for a New Age of Journalism.]

How do readers respond the emphasis on local?

Robinson: "… I hear from some who bemoan the lack of Washington coverage and foreign news, but they are often readers who have a political ax to grind. For instance, we didn't publish a story on the British intelligence report on Bush's decision to invade in 2002. (We should have, too, inside.) I heard from some folks who insisted we should have published the story across the top of the front page to show Americans the true colors of the president. But these folks, of course, already knew about the story from elsewhere so they weren't criticizing us for not giving them the news, they were criticizing us for not helping other citizens understand the world the way they understand it."I don't think, though, that our readers truly miss the wire service reports. I know they don't miss the Times news reports because we publish so few of them. They come in too long and too late. And, you raised the question of whether readers pay attention to the source of non-local news? I submit that they not only pay no attention to the source of a wire report, they also pay no attention to bylines, local or otherwise."

Note Robinson's comment about the value of the Times reports to his paper: "They come on too long and too late." One size of journalism does not, not should it, fit all.

Does the concept still apply that every paper, regardless of size, should be a "full service" newspaper, offering a buffet of local, national and international news as well as business, sports and entertainment?

Robinson: "People who've grown up with newspapers want the full-service options. They don't use the Internet much. They watch TV but it's gotten so frivolous in so many ways. So they rely on us. But, as you and others have noted, we can't rely on them to carry us into the future. I need to produce a newspaper that is unique, that does what no other media outlet in my community does. To me, intensely, exclusive local content is part of that."… We still expect to be a grocery store of a newspaper - a place where someone can come in a shop for the items that interest them, whether it is local editorials, a contentious City Council argument, the astrology column, a department store ad, a high school football game preview, a "neighbor you should know" or an investigative report. But if he or she wants the 50-inch write-thru on the Bolton nomination, you're going to have to go to the gourmet store across the street and get it. (And the Sunday Times costs $5.40 here vs. $1.25 for the News & Record.)"

I have been using the full-service metaphor somewhat as a negative because it embraces the mass medium and I think newspapers must move away from trying to be provide something for everybody (mass) toward focusing on more for fewer (class), but I do like Robinson's grocery store-gourmet shop distinction.

How do you decide which national copy to keep and which to jettison?

Robinson: "Editors here are in the process of rebuilding this newspaper. We're talking about reducing national and international content to a page or two. We're experimenting with the glocal idea. (It's damned harder, though, than the essayists make it, we've found.) We're looking hard at the stock pages. With UNC, Duke, Wake, N.C. State, UNCG, N.C. A&T and three other colleges with Div. 1 sports programs within 60 miles of us, we consider major college sports local. But coverage of pro sports in any significant way is being examined. (We have already eliminated much of it.) I blocked the idea of a local movie reviewer a couple years ago because I believed that movie reviews didn't need to be local and that, in fact, we could get better reviews from the wires. I still believe that."

This is a good place to note for the record that change is hard work, and it is "damned harder" for editors like Robinson to make it happen than it is for sideline coaches like me to urge them to do it. That's why it is so important that within the newspaper industry we share the lessons learned with each new experiment, with every bold step taken, so the effort of the early adopters of change provides benefit for all. It is a conservative business and many will not venture forth into the future until others have broken a trail and declared it passable.

What do substitute for wire copy? You can't simply hire more local reporters.

Robinson: "As you note, the key question is: if we drop the national and international wire stuff, if we drop the stocks, how do we fill the space with local. … We aren't willing to whip our staff any harder to produce more copy. And re-jiggering assignments can only get you so much. … So, our expectation is to create what we've called a town square, but what you would identify as citizen journalism, I guess. We hope to create communities of geography in the towns surrounding Greensboro, using community columnists and citizen reporters to write about what's happening in their area. We hope this will feed an OhMyNews model that we hope to establish online and in the newspaper."

What about the Times columnists? You mentioned on your blog that they were one of the biggest appeals of the Times news service.

Robinson: "… I'm less sure that my logic holds. I'd be more confident about replacing all the syndicated columnists if I knew we could replace them with equally cogent and insightful local writers. ... I'm getting dozens of e-mails and phone calls appealing to me to reconsider the cancellation of the Times News Service solely based upon the importance of Tom Friedman's column. I like Friedman's voice, too, so I understand what the loss of it means. On the other hand, he's in hundreds of other papers and available online free (for a little while). So, I don't know where I am on that."

At another point, Robinson wrote in his blog that "virtually all the people who've written to me have singled out Thomas Friedman as the item they will miss. While his voice was valuable to us, at $34,000 a year -- with a 10 percent increase this year -- the news service became impossible to justify."

(He added that the Baltimore Sun made a similar decision about the Times in January and received a similar response about Friedman. "We attempted to negotiate separate purchases of columnists, but it was a non-starter with the Times syndicate," Robinson said when he announced the decision.)

What does your decision about the Times say about the direction you want the News-Record to go?

Robinson: "In the end, we've decided that our newspaper has to move. It has to become more distinctive, more interesting, more reader-friendly. Last month, the managing editor and I decreed that we weren't publishing any more boring stories. That didn't mean we didn't want the government process stories. It means that we expect reporters and editors to report and write them in ways that are compelling and relevant. (We're still working on that.) But we think readers will move with us. Traditional readers want many of the same things that infrequent readers want: shorter stories, bigger photos, more 'news-to-use' information, more investigative reports, more stuff to talk about."

Spot stories about institutions - meetings, reports, process - and stories about crime typically make up between two-thirds and three-quarters of all newspaper coverage. Count them in your local paper over a couple of weeks. Is this where we should be spending our increasingly precious journalistic resources?

What larger issues in journalism are you trying to address?

Robinson: "Newspaper journalists have two challenges: First, we need to get over ourselves. The journalism that we consider important is still important, but we need to write it for readers not ourselves. So it needs to be shorter. And we need to use different storytelling methods. … Second, we need to take more chances. We need to pay attention to the data. We need to change our direction and absorb the complaints by readers. We need to try more things."And we certainly don't need to dumb-down our content or water down our commitment to the fundamentals of journalism."

Great advice: Get over ourselves, take more chances and don't abandon our core mission.

Tags: Journalism, Newspapers, Media