Anyone who has worked in media knows the end product — magazine, newspaper, film — represents a series of choices and decisions made by individual creators, the team as a whole and, increasingly in films, the audience. (And, of course, web-based media like You Tube or Fark is almost wholly based on audience selection.)

Anyone who has worked in media knows the end product — magazine, newspaper, film — represents a series of choices and decisions made by individual creators, the team as a whole and, increasingly in films, the audience. (And, of course, web-based media like You Tube or Fark is almost wholly based on audience selection.)

How much weight your decision carries in influencing the final result is often relative. When I ran newsrooms, I had little control over what the creators — the writers and photographers — chose, but quite a bit more over the final product.

Now that I’m freelancing again, I have creative control over how I shoot something, but less to say about how the photo is going to be used or even which one from a shoot will run in , let’s say, a magazine. I have learned, though, how to shoot things differently for different clients — some like light glossy and bright colors, others prefer darker, edgier shots. I shoot to match their style, then always add in some preferences of my own.

The above picture of Samantha Paris, who runs a voice-over training school in Sausalito, provides some good examples of the choices I made in photographing her and the decisions my client, in this case Marin Magazine, made in using the photographs.

I stopped by Samantha’s studios while the writer was interviewing her, just to look the place over and meet her. As soon as I saw the recording booth, I knew I wanted to shoot her in there, but also knew I’d be pushing my technical skills because the space was so tight (about 3 feet by 5 feet) and so dark.

I wanted to use the shapes of the microphone and the pop screen as graphical elements and also have a spotlight effect to the photo. The booth had a window in front so the actor and sound engineer could see each other and I decided to use one light to shoot through that window.

At home, I blocked out a space in my living room similar to the size of the booth, and saw that I could get another light stand in the back corner of the booth and a shorty studio stand on the floor behind Samantha. I did some tests shots and felt I at least had technical control of the shot.

For the shoot itself, I used three SB800s — the one outside the window,the one in the booth corner and the one on the floor. The main and hair lights had snoots and CTO gels to warm up Samantha (not that her personality needed it) and the background light had a blue gel.)

We shot for about 30 minutes in the booth, including a sequence in which she acted out some scenes (left).

We shot for about 30 minutes in the booth, including a sequence in which she acted out some scenes (left).

I also wanted to make some pictures of Samantha interacting with her students, so we set up some chairs in a front room with a big window and I shot about 20 or 30 frames using the natural light.

Afterwards, looking at the files, I was pleased with the shots in the recording booth (although I did underexpose by a half-stop), but I was pretty sure the magazine would use the more informal and more interactive shots with the students. I also liked the shots of in the booth more when she wasn’t acting and just looking at the camera.

I got first indication of which way the magazine’s choice would go later when my wife, a former journalist, looked at the take and loved the acting shots and those of Samantha with the students.

She was an audience focus group of one and her instinctive response mirrored the one the magazine editor made later. The image below of Samantha and her students, ran big. The “acting” shot ran smaller. My favorite (at the top of this page) didn’t make the cut.

Is there a lesson? Yes, and it’s that we shoot (or write) for many audiences — the audience of one (ourselves), the audience of many (readers, viewers) and the audience of economics (our clients). I love it when they overlap. When they don’t, I cash the check anyway.

sometimes calls “photo crap” — i.e., gear — is involved in making what becomes a simple white background image when printed. Here there are five lights, three of which you can see and two others behind the black foam boards pointed at the background.

sometimes calls “photo crap” — i.e., gear — is involved in making what becomes a simple white background image when printed. Here there are five lights, three of which you can see and two others behind the black foam boards pointed at the background.

Just a quick post on this portrait because I am jamming to finish a couple of magazine projects before I head out of town for a working vacation — to the wedding of a friend in Cartagena. Vive los novios!

Just a quick post on this portrait because I am jamming to finish a couple of magazine projects before I head out of town for a working vacation — to the wedding of a friend in Cartagena. Vive los novios!

Anyone who has worked in media knows the end product — magazine, newspaper, film — represents a series of choices and decisions made by individual creators, the team as a whole and, increasingly in films, the audience. (And, of course, web-based media like

Anyone who has worked in media knows the end product — magazine, newspaper, film — represents a series of choices and decisions made by individual creators, the team as a whole and, increasingly in films, the audience. (And, of course, web-based media like  We shot for about 30 minutes in the booth, including a sequence in which she acted out some scenes (left).

We shot for about 30 minutes in the booth, including a sequence in which she acted out some scenes (left).

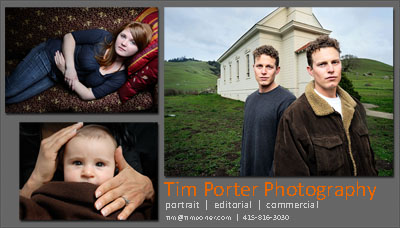

This is a story about a simple picture gone wrong and why a do-over is sometimes the right thing to do.

This is a story about a simple picture gone wrong and why a do-over is sometimes the right thing to do. Later, looking at the shoot in the computer, I kept thinking, “How could I blow a shot of a baby.” All I wanted was

Later, looking at the shoot in the computer, I kept thinking, “How could I blow a shot of a baby.” All I wanted was