Whenever I teach, as I’m doing this summer in a short class on action photography at The Image Flow in Mill Valley, I find two things to be the most challenging: Explaining to others what I do instinctively in a way they understand and not knowing what the students don’t know.

The first forces me to think in granular terms about what I do with the camera — and why. For example, one student asked me why I usually use ISO 400 as my base setting when most digital cameras have ISO settings lower than that. Well, I answered, somewhat lamely, it’s because I grew up on Tri-X, Kodak’s legendary black-and-white film. It had an ASA of 400 and my earliest lessons about light and manual exposure were learned using that number as a base — and those lessons still work today. In other words, it’s a habit, albeit one that serves me well.

The first forces me to think in granular terms about what I do with the camera — and why. For example, one student asked me why I usually use ISO 400 as my base setting when most digital cameras have ISO settings lower than that. Well, I answered, somewhat lamely, it’s because I grew up on Tri-X, Kodak’s legendary black-and-white film. It had an ASA of 400 and my earliest lessons about light and manual exposure were learned using that number as a base — and those lessons still work today. In other words, it’s a habit, albeit one that serves me well.

The second challenge is more difficult. What each student knows about photography in general and the intricacies of their own camera in particular varies widely.

Most, not surprisingly, came to photography in the digital age and with cameras so advanced and so automatic that they skipped the need to studdy the basics of photography, so they have a poor understanding of the connections between light and exposure, between shutter speed and aperture, and between focal length and depth of field.

They all have inexpensive lenses that in a short twist of the barrel leap rom wide-angle to telephoto, so they’ve never had to master the physical art of moving through a scene with prime lenses in order to change the point of view or to get closer to or farther from a subject.

Because of these gaps, each time I attempt to explain something more advanced, such as capturing the fleetness of a runner with a pan or freezing the motion of boy on bike in a half-pipe, it opens the door to a more basic discussion about the principles behind the technique and where to find the buttons and dials on a particular brand of camera in order to get the technical stuff right.

For this reason, I learn along with my students. I learn about my own habits (good and bad), I learn how different types of cameras work (even their Nikons don’t function as mine does) and, most importantly, I learn I need patience in order to succeed — and that’s a lesson that applies to photography as well as teaching.

Put 10 or 12 people in a dark coffee shop, add in a freelance writer, a magazine editor, a roomful of customers and a couple of homeless people in the back, and you’ve got a scene.

Put 10 or 12 people in a dark coffee shop, add in a freelance writer, a magazine editor, a roomful of customers and a couple of homeless people in the back, and you’ve got a scene.

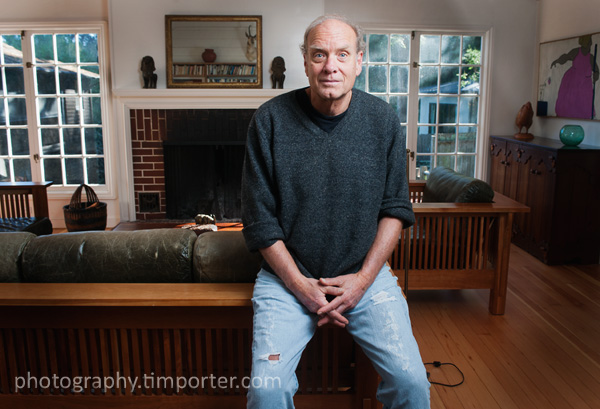

Four decades later when I met Harris in his Mill Valley home I was a bit intimidated and hoped I could make a picture worthy of my opinion of him, which when I left 45 minutes later I wasn’t sure I had (but I was even more self-critical in those days than I am now — something those who know me well might find hard to believe).

Four decades later when I met Harris in his Mill Valley home I was a bit intimidated and hoped I could make a picture worthy of my opinion of him, which when I left 45 minutes later I wasn’t sure I had (but I was even more self-critical in those days than I am now — something those who know me well might find hard to believe).

sometimes calls “photo crap” — i.e., gear — is involved in making what becomes a simple white background image when printed. Here there are five lights, three of which you can see and two others behind the black foam boards pointed at the background.

sometimes calls “photo crap” — i.e., gear — is involved in making what becomes a simple white background image when printed. Here there are five lights, three of which you can see and two others behind the black foam boards pointed at the background.