It is unsettling to me, someone who has spent the better part of his doing one form of journalism or another, that the brazen embrace of The Big Lie by politicians has become so prevalent that those of us who prefer facts over fiction find ourselves making a case for the importance of truth.

It is unsettling to me, someone who has spent the better part of his doing one form of journalism or another, that the brazen embrace of The Big Lie by politicians has become so prevalent that those of us who prefer facts over fiction find ourselves making a case for the importance of truth.

Certainly, the rise of Donald Trump from Manhattan con man to Tweeter-in-Chief and the both intentional and unwitting acceptance by his stooges and other supporters of his fact-free self-serving version of reality has not only fueled the outrage more than half of America feels about their incoming president’s manipulative use of the lie, but has also confronted journalists with a challenge they are increasingly lesser-equipped to face in this age of declining revenue: How to shine the light of truth onto the dark web of lies woven by Trump and his ilk.

I found one answer to this question in the unflinching photography and reporting by photographer Daniel Berehulak in today’s New York Times about the brutal ant-drug campaign by Philippine Rodrigo Duterte.

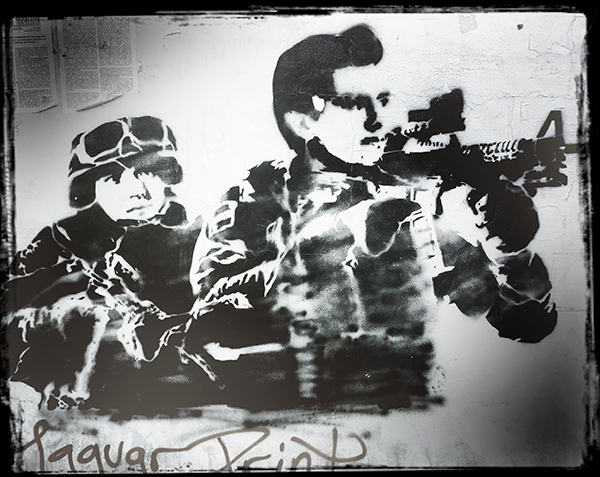

Duterte has unleashed his nation’s police and armed forces on the citizenry. More than 2,000 Filipinos have been killed by authorities since June 30, when he took office, and another 3,500 slain in other unsolved murders. The slaughter – the word used in the headline of Berehulak’s piece – continues with impunity with each murder wrapped in an official lie. The dead, as described in police reports, are often accused of “nanlaban,” which Berehulak describes as “what the police call a case when a suspect resists arrest and ends up dead. It means ‘he fought it out.’ ”

Berehulak’s report, and his savagely honest images, expose Duterte’s lie. Will the truth deter Duterte and save lives? Probably not. But it informs us, we Americans who must now live in nation led by a man whose first instinct is self-preservation and whose first tool is the lie.

Trump and Duterte talked by phone a week ago. Trump applauded Duterte’s brutality and invited him to the U.S. Liars are attracted to one another (see Trump’s bromance with Vladimir Putin). They need – and use – one another as partners and foils against the truth.

Trump is mendacious (to say the least) and not murderous (for now), but his looming occupancy of the presidency highlights like never before in recent American history the need for truth and its importance to civil society and our democracy.

What can each of us do? One thing is to demand hard truths from journalism and support journalists and news organizations that deliver it. Many Americans are already doing this, as evidenced by the 70,000 new subscribers the New York Times has enrolled since Trump’s election. Truth comes with a price. If we want the truth that we need, then we must pay for it.