Two words summarize my reading in 2025: disappointment and distraction.

I abandoned only three books out of seventy-six, but many others left me wishing I’d done something else with my time. At fault, it seems to me, is the plethora of newer authors who are not only poor storytellers but equally mediocre writers. They create books made for visual streaming, heavy on dialogue, short on exposition, absent of character depth. Publishers churn out these fast-lit titles and package them in breathless blurbs hoping to gain footing on celebrity or other “best-of” lists. Too often the hype is just hyperbole.

Add to this an elevated state of personal distraction rooted in the perversions of the current occupant of the White House as well as homefront complications that resulted in shortened leisure time and shattered an already compressed attention span.

The result: fewer books (76 in 2025 vs. 100 in 2024) and less satisfaction.

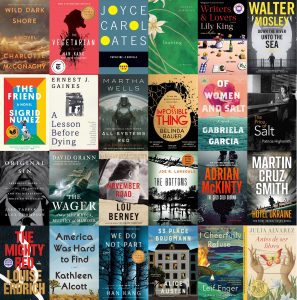

Nonetheless, I managed to read to a number of wonderfully written and narrated books. Five of my favorites:

- Wild Dark Shore (Charlotte McConaghy) – an enthralling story of nature’s ferocity and mankind’s duplicity.

- The Impossible Thing (Belinda Bauer) – goodness and avarice clash in this tale of a treasure that survives through persistence and ingenuity.

- The MightyRed (Louise Erdrich) – a story about the value of authenticity and acceptance disguised as a love triangle.

- The Vegetarian (Han Kang) – a very human book that is uncomfortable to read, but rewards those who find solace amid distress.

- America Was Hard to Find (Kathleen Alcott) – an expansive novel of the shifting cultural tectonics that ruptured America in the 1960s, part requiem, part eulogy for an epoch.

Others just as good: November Road (Lou Berney); Hotel Ukraine (Martin Cruz Smith); The Bottoms (Joe R. Lansdale); A Lesson Before Dying (Ernest Gaines); and, Leaving (Roxana Robinson).

I discovered audiobooks while taking long, solo walks during the Covid confinement. I still mostly listen while I walk. For me, the narrator is everything and when I discover one I like I tend to binge a series. Hence, this year:

- Adrian McKinty’s tales of Northern Irish cop Sean Duffy: The Cold Cold Ground; I Hear the Sirens in the Street; In the Morning I’ll Be Gone; Rain Dogs; Police at the Station and They Don’t Look Friendly; and, The Detective Up Late.

- Walter Mosely’s addictive story of Joe King Oliver, a railroaded NYPD detective: Down the River Unto the Sea; Every Man a King; and, Been Wrong So Long It Feels Like Right.

- Finally, there is, to me, no finer narrator than George Guidall, who reads (among many other books), Craig Johnson’s stories of Absaroka County sheriff Walt Longmire. This year I listened: An Obvious Fact; The Western Star; and, Depth of Winter.

At my age, I set few goals (I’ve already accomplished most of what I could and hold no regrets for what I couldn’t). That said, here’s one: I will do my best to ignore the world’s noise and devote more attention to the inner tranquility I find in books.

The List:

- Yellowface – R.F. Kuang

- The Most – Jessica Anthony

- A Lesson Before Dying – Ernest Gaines

- As the Crow Flies — Craig Johnson *

- Don’t Believe It – Charlie Donlea

- Down the River Unto the Sea — Walter Mosley *

- Of Women and Salt – Gabriela Garcia

- The Friend – Sigrid Nunez

- Every Man a King — Walter Mosley *

- The Last Days of Ptolemy Gray – Walter Mosely *

- All Systems Red: The Murderbot Diaries – Martha Wells

- The Last King of California – Jordan Harper

- Patricide: A Novella – Joyce Carol Oates

- Peace Like a River – Leif Enger **

- All the Colors of the Dark – Chris Whitaker

- The Price of Salt – Patricia Highsmith

- The Drop – Michael Connelly *

- Leaving – Roxana Robinson

- Been Wrong So Long It Feels Like Right – Walter Mosley *

- Foregone – Russell Banks

- Lazarus Man – Richard Price **

- Roseanna — Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö

- The Martian – Andy Weir

- Open Season – C.J. Box *

- Savage Run – C.J. Box *

- A Drink Before the War – Dennis Lehane

- Original Sin – Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson

- The Neon Rain – James Lee Burke *

- The Wager – David Grann

- Heaven’s Prisoners – James Lee Burke *

- Writers & Lovers – Lily King

- Winterkill – C.J. Box *

- I Cheerfully Refuse – Leif Enger

- The Vegetarian – Han Kang

- 33 Place Brugmann – Alice Austen

- Never Flinch – Stephen King *

- We Do Not Part – Han Kang

- The Gray Anarchist – Jeffrey Marcus Oshins *

- The Cold Cold Ground – Adrian McKinty

- An Obvious Fact – Craig Johnson *

- The Last Flight – Julie Clark

- I Hear the Sirens in the Street – Adrian McKinty *

- The Bottoms – Joe R. Lansdale

- The Invention of Solitude – Paul Auster

- In the Morning I’ll Be Gone – Adrian McKinty *

- We Had to Remove this Post – Hanna Bervoets

- Heartwood – Amity Gaige

- Desert Star – Michael Connelly *

- The Tattooist of Auschwitz – Heather Morris

- The Emperor’s Children – Claire Messud **

- King of Ashes – S.A. Cosby

- Antes de Ser Libres – Julia Alvarez

- Tides – Sara Freeman

- At What Cost – James L’Etoile **

- The 6:20 Man – David Baldacci *

- Rain Dogs – Adrian McKinty *

- The Mighty Red – Louise Erdrich

- Trophy Hunt – C.J. Box *

- And Then There Were None – Agatha Christie *

- The Impossible Thing – Belinda Bauer

- Elizabeth Finch – Julian Barnes

- Police at the Station and They Don’t Look Friendly – Adrian McKinty *

- Hotel Ukraine – Martin Cruz Smith

- Lilith – Eric Rickstad

- Wild Dark Shore – Charlotte McConaghy

- The Black Box – Michael Connelly *

- America Was Hard To Find – Kathleen Alcott

- The Western Star – Craig Johnson *

- November Road – Lou Berney

- Depth of Winter – Craig Johnson *

- After the Lights Go Out – John Vercher **

- The Librarianist, Patrick deWitt

- The Detective Up Late, Adrian McKinty **

- The Long and Faraway Gone, Lou Berney

- The Trouble Up North, Travis Mulhauser **

- Abscond: A Short Story, Abraham Verghese

* Audio

** Did Not Finish