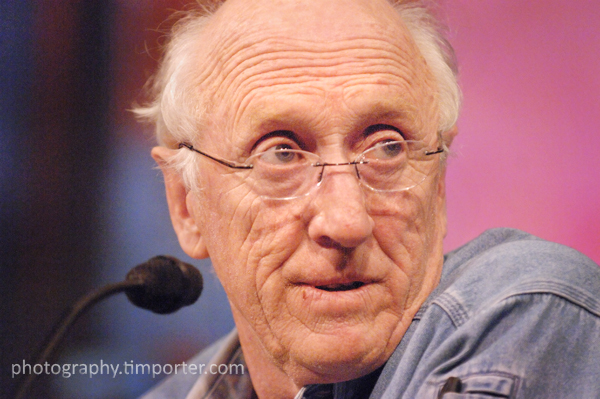

Stewart Brand at the Bioneers conference, 2007

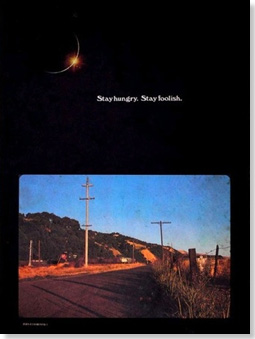

“Stay hungry. Stay foolish.”

That farewell maxim from the final issue of the Whole Earth Catalog encapsulated the message Steve Jobs delivered in his now famous 2005 Stanford University commencement address. With Jobs’ death, the words have gone viral.

The sudden resonance of that 40-year-old quote lies in part to its momentary revival of social awareness in Boomers who have slipped into the mental dormancy of their seventh decade. More than that, though, it was welcomed into the hearts of an iGeneration who has come of age in an hour when the promise of a bright digital future is obscured by the persistent fog of a dismal global economy, a stagnant and hostile political state, and a well-founded anxiety that their time is passing before they ever had the opportunity to take advantage of it.

They voted for Barack Obama because he offered hope and change. They eulogize Steve Jobs because he gave it to them.

The intellect behind the Whole Earth Catalog belongs to its co-founder and editor, Stewart Brand. After Jobs died, I Googled my way through Brand’s life and rediscovered a man whose impact on the ideas and sensibilities shaped — and continue to shape — a broad swath of the world we live in. His footprints are embedded on constructs as diverse as electronic social communities (The Well) to strategic corporate thinking (Global Business Network) and the current debate about the use of nuclear power as a long-term energy solution (here’s the book).

Given all that, Brand had a bit more to say than “stay hungry, stay foolish.” Here, then, are some other quotes from Brand. Maybe they’ll compel you to learn more about him (or to reacquaint you with what has slipped out of memory).

* “Information wants to be free.” Often cited by those who believe ownership of digital content is universal, it was part of larger statement in which Brand also said, ” … information wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable.” Here’s the whole story.

* “You own your own words, unless they contain information. In which case they belong to no one.” The sign-on message of The Well.

* “A library doesn’t need windows. A library is a window.”

* “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

* “Civilization’s shortening attention span is mismatched with the pace of environmental problems.”

And, perhaps my favorite:

* “Once a new technology rolls over you, if you’re not part of the steamroller, you’re part of the road.”

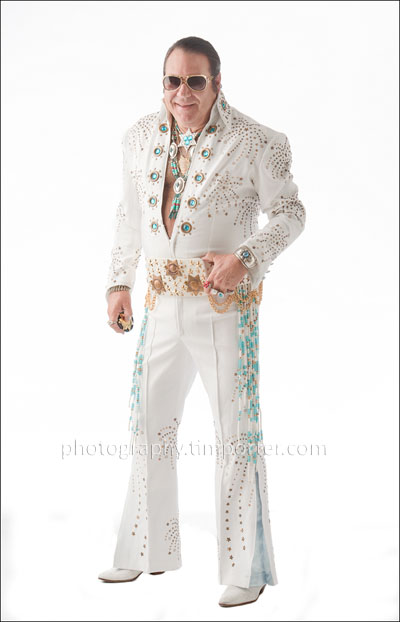

sometimes calls “photo crap” — i.e., gear — is involved in making what becomes a simple white background image when printed. Here there are five lights, three of which you can see and two others behind the black foam boards pointed at the background.

sometimes calls “photo crap” — i.e., gear — is involved in making what becomes a simple white background image when printed. Here there are five lights, three of which you can see and two others behind the black foam boards pointed at the background.