How was Oaxaca? That’s what everyone asks each time I return. It’s a polite, succinct question and what’s expected in return in the form of an answer is something similar in character, such as: “It was great, thanks.”

How was Oaxaca? That’s what everyone asks each time I return. It’s a polite, succinct question and what’s expected in return in the form of an answer is something similar in character, such as: “It was great, thanks.”

And after dozens of trips to Oaxaca I’ve learned to limit my answer to what people are expecting, sometimes adding a short augmentation: “It was great, thanks. Complicated, but great.”

Most folks leave it at that and move on in the conversation because in reality only a small percentage of our fellow humans want to hear about our vacations (even though for me Oaxaca is not a vacation; nonetheless, most of my friends see it that way).

The other day, though, someone asked me in Spanish about my recent trip, from which I returned home a week ago, and when I delivered my stock answer she then asked: What do you mean when you say complicated? Qué quieres decir cuando dices complicado?

So, I told her.

I told her about the single mothers from the children’s shelter that was closed nearly a year-and-a-half ago when the state accused the founder and her family of mismanagement and physical and sexual abuse. I have stayed in touch with some of the mothers and continue to photograph some of them and their kids.

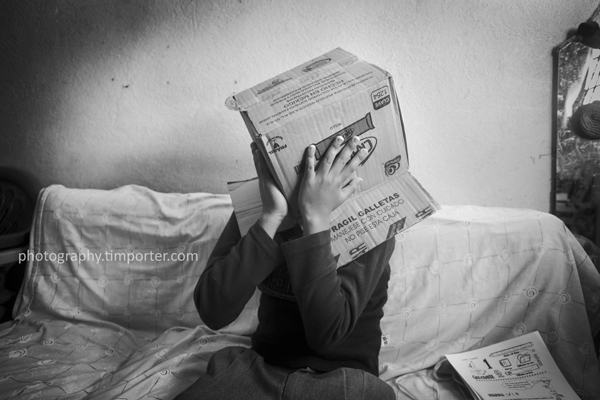

One of the mothers has put her son and daughter in two others shelters run by the Catholic church and now lives in a 12-by-12 room paid for by an older doctor who seems to use her for sex and companionship but doesn’t want anything to do with her kids. The children are the product of a marriage that went bad when the husband’s business failed and he began to drink. He beat her, locked her in the house and made her dress like a man so that other men wouldn’t look for her. I took her to lunch and when we walked by the house in which I rent a room she sat on the steps and began to cry, saying the beautiful colonial building reminded her of the happy life she had before her husband became violent. On the day before I left, we met again briefly in a tiny chapel near her room so I could see her daughter. The doctor won’t let me visit where she lives. He appears to be jealous. The daughter has grown taller in the year since I last saw her and in the chapel she modeled a paper mask she’d made in school as her mother and I sat in a pew. I made a few frames of the girl. The mother took my hand and we sat in silence.

Another of the mothers lives outside of the center of town. She works every day, cleaning houses in the morning, cooking food in the afternoon to sell at her daughter’s school during recess and doing haircuts in the evening. She and her kids – a 13-year-old boy and an 11-year-old daughter – also live in a single room, this one about 10 by 15, for which they pay 600 pesos a month. The neighborhood is poor-ish and safe except for one thing: There is a guy on her block who is killing cats and dogs. He poisoned this mother’s two dogs and then her cat. When the mom got another dog, he ran it over in the street and left it to die from suffocation, the result of its shattered ribs piercing its lungs. The mother wants to make a poster to hang from the front of her building that will say: Beware! We have a neighbor who kills.

The mother has a new dog now, the uncle of one of the dead ones. To keep the dog from being killed, she keeps it on a small plot of land owned by a friend. We walked there one morning carrying a heavy plastic pot of gruel made from noodles, tortillas and rice and a bag of day-old bolillos – dogs love bread, she told me. It’s a 45-minute slog, most of it up a steep hill. What I lacked in breath when I got there, I gained in view. A half-dozen dogs live on the land, which also features an unfinished cement house. She fed the dogs the bread and gave them water she’d collected from a well we passed on the route, hung around for about 10 minutes and began to walk back. Ninety minutes of walking for 10 minutes of dog time. She loves this dog as much as she hates her murderous neighbor.

A third of the mothers I’d only met a few months ago. She is a smart, street-savvy, tattooed young woman with a 5-year-old boy. This trip we met in her aunt’s house, which sits a dusty rise overlooking the west side of the Oaxacan valley. The house is new, built of cinder blocks and concrete – all of it gray. The floor, the walls, the ceiling – all of it unfinished concrete. Were it not a two-story structure located above ground, it would seem like a bunker. An impressive black-and-gold metal door fronts the street. The second floor has a terrace. The roof grants an immense vista. The house is the product of 14 years of work in a San Diego suburb by the aunt’s husband, who she last saw five years ago. They have two children, a boy 14 who wants to study gastronomy and another boy 5. The father needs another year or two in the States to finish the house.

What else?

There were the mother and the father and their four daughters who drove two-and-a-half hours to Oaxaca, much of the journey over sinuous dirt roads, to pick up a photographer friend and I and then continued driving another two-and-a-half hours to the lovely mountain town of Capulálpam so that two of those daughters – the two who aren’t twins and who aren’t deaf – could participate in a folk dance festival that didn’t end until well after nightfall. Ten hours of vomit-inducing driving (not for them, but for me) in a 25-year-old car so their kids could dance. Don’t talk me about how American parents support their children until you meet this family.

There was the day at the horse races in the countryside when I met a fierce looking cowboy whose buddies had nicknamed Bin Laden because, well, because he looked just like the dead Al Qaeda leader. The whole group of them was pretty far drunk when I stumbled upon them. My presence triggered a round of jokes and insults, which didn’t stop until one of the largest of them told me he had a big dick and asked me if mine was bigger. When I answered that I didn’t know, but that he could ask his mother, all his pals roared and one of them offered me a beer. Ice broken.

There was night at the dances when another mother, this one a tall beauty from a farm town who had returned to Mexico after living with her three U.S.-born kids in Chicago and New York for more than a decade, put on a beautiful huipil from the Pinotepa and danced with the other moms from her kids’ primary school carrying pineapples.

There was the lunch on a Sunday in another farm town, where I ate outside the cinder block-and-lamina home of a teen-age girl who is about to graduate from high school – the first in family to do so – during which she told me, as she looked at her two grandmothers seated at the wobbly table: This is why I wanted to come back to Mexico from Los Angeles; my friends there talked about things they did with their grandmothers and I never had that. Now I do. … I couldn’t hide my tears.

There was the nauseous van ride to a valley a few hours east of Oaxaca where a religious man, who with wife runs another children’s shelter, is building a massive round church in the butt end of lush green canyon split by a river that provides the only relief from the valley’s oven-like temperatures.

There were the new kids at the other shelter in Oaxaca – three 3-year-old triplets and a 6-year-old boy whose sweet disposition and engaging smile belie the abuse he’s clearly suffered. At age 6, his legs remain infant-like, soft, flexible and too weak to be able to walk. He cannot talk. He has the height of a 3-year-old (although some of the hardness of facial features betray his years).

There was – as always – the food: The entomadas in Ocotlán, the chilaquilies one of the moms made on the stove in her room; the vegetable soup eaten with the grandmothers; the 40-peso plate of tasajo, frijoles and onion in another market, the nieves in the plaza (several times) and the mescal, the mescal and the mescal.

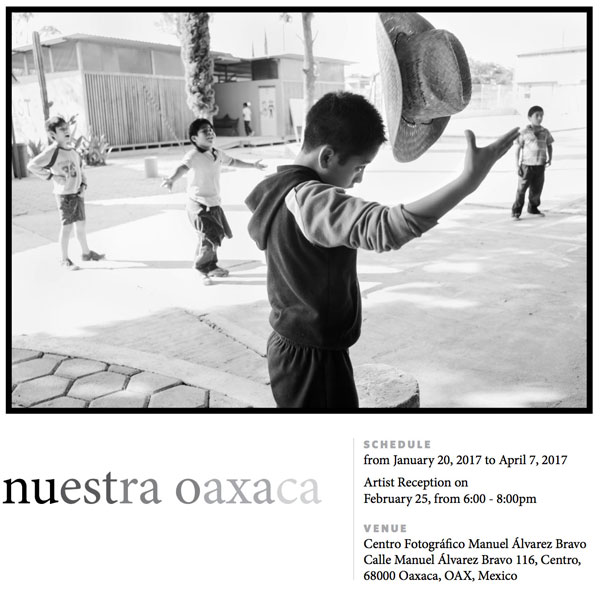

And there was the photo exhibition at the Centro Fotográfico Manuel Álvarez Bravo – the reason for making the trip at this time. Seven of us went, those participating in the show, as well as a few spouses and friends. We talked one evening at the gallery (although I mostly croaked, the sound effect of a bad cold), ate together much more, went shooting together and left, well, I’m not sure how we left. We’ll see what next year brings.

How was Oaxaca? I’m so glad you asked.

OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer

OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer