A teenage boy dies in Mexico. Tragic, so young, you might say, but also so common. In a land of violence and poverty, the lives of young men meet regrettable ends with common frequency. The story of this boy, though, is special. I will tell what I know of it, but there is much more outside of my knowledge. First, his name. It remains with me. After enduring so much in such a short life, he deserves privacy, as do his parents. In this story, he is Kiki, and they are Guadalupe and Miguel.

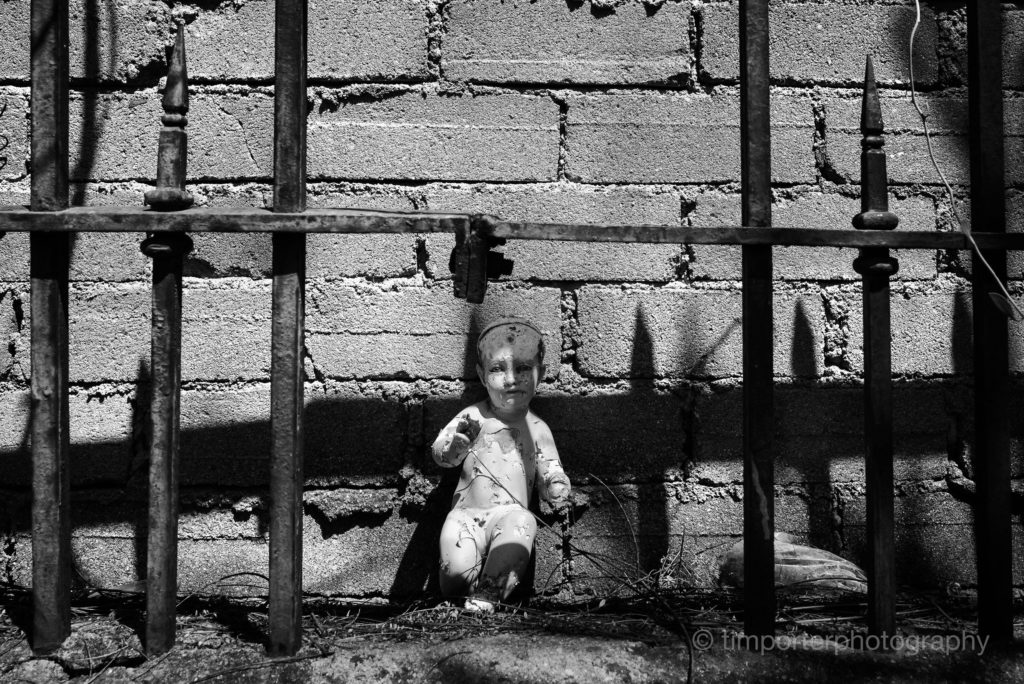

Kiki’s troubles began even before he drew his first breath. As he crowned out of his mother’s birth canal, the attending doctor, who was unskilled, grabbed awkwardly, twisting the emerging boy’s head and damaging his spinal column. Kiki’s brain survived, but its connection to his extremities and his organs did not. Kiki saw and heard, but he could not control. His limbs contorted into a permanent S, and his hands and feet curled inward, in retreat from his body. His speech consisted of an array of sounds – sweet gurgles, anxious pleadings, rhythmic mouthing to the music he loved. Stunted in height and thinned by lack of muscle, he weighed no more than a first grader.

Atop this anatomical mess sat Kiki’s full-sized, beautiful head. His face was broad across the cheekbones, full around the mouth, punctuated by an assertive nose, and adorned with a pair of deep, dark, hypnotic, ovular eyes that spoke all the emotions that Kiki’s muted voice could not – sparkles for pleasure, tears for sadness, and long, unblinking stares that could have been inquisitiveness or maybe just incomprehension. From the neck up, he was as attractive as he was grotesque from the neck down.

Kiki lived in a rural village that was near a bigger city, but still remote enough that a visitor from a more developed world could walk the town’s only paved road, smell the fields of garlic that surround it, pass the empty church (closed by an earthquake that cracked its tower), and imagine being in another century. Only the satellite dishes jutting up from rooftops broke the reverie.

Guadalupe, Kiki’s mom, is a short, quiet, doe-eyed woman whose dominant expression is one of permanent suspension, of canceled expectation. Her face is young enough to still hint of the coquettish beauty of her youth, while portraying the weight of caring for Kiki for a decade and a half, feeding, bathing, dressing, changing the bag he needed to empty his waste. A deep, vertical furrow creases her forehead about her broad nose. Miguel, the father, missed most of Kiki’s life. He was in California, working in a restaurant, sending money home, but also indulging himself with dalliances in adultery and drinking. By the time Miguel returned to Mexico, he was rotting from the inside out; diabetes, brought on by the drinking, was dissolving one gangrenous leg and eroding his eyesight.

Kiki outlived his father, who died blind and minus half a leg at age 49, one more victim of a disease that plagues Mexico. In the weeks before his death, Miguel laid in a single, metal-framed bed next to that of his son, to whom he spoke in the rhythmic Spanish of the Mexican countryside. Miguel’s final act of life was to teach Kiki how to say his father’s name. I saw Guadalupe a few weeks after Miguel died. As she sat on her bed holding Kiki in her lap, she told me he was speaking his father’s name. I couldn’t understand it, but she and Kiki did. That was what was important.

When Miguel died, Kiki cried for three weeks. Silently. He had grown accustomed to hearing his father’s voice and feeling his presence in the room with him. He could not have known his father was dying, though I am sure he realized Miguel was his father because he was aware of who people were – his mother, of course, the grandmother who lived with him, and occasional visitors from other places. Three weeks of tears, three weeks of mourning.

The bed-bound intimacy of the dying, diabetic father and his physically crumpled son was, despite the hardship of caring for both of them, a gift of emotional honesty for Guadalupe, who for her entire period of motherhood was ensnared in a web of whispered lies and unspoken truths, the result of the duplicitous actions of her husband.

Kiki was Miguel’s third child. His first was born in California to a woman he met there. A boy or a girl, I don’t know. The mother of the second child was a local woman from the same town as Miguel and Guadalupe. They liaised long enough for her to give birth to a boy, and then Miguel’s libidinous eye landed on Guadalupe, a curvy young woman with lush black hair, a good-looking country girl. When Miguel proposed to Guadalupe, her family balked. The whole town knew he was a philanderer. Who could say if something as fragile as a marriage vow would bind him to monogamy? He persisted, though, and what followed was marriage, pregnancy, and Kiki.

By the economic standards of the village, which border on poverty, Kiki’s family made enough money for a decent life. They had a plot of land, good for growing food. Miguel sent home dollars from California, that enabled them to open a sparsely stocked hardware store. There were even pesos to pay for physical therapy for Kiki. What fortunes they had, though, flagged after Miguel’s return. First hobbled and then blinded, he was limited to simple domestic chores, such as scraping kernels of corn off dried cobs. When money got tight, therapy for Kiki stopped.

As his eyesight retreated into narrow tunnels of vision, Miguel passed hours seated in a plastic chair in front of the hardware store, whose eastern side was shaded from the afternoon sun and faced a vacant lot about the size of a soccer field that bordered the town’s church. On the south end of this land, opposite the front door of the hardware store, Miguel sunk a large wooden pole into the ground, and to the pole he tied a horse. On sunny afternoons, a boy walked over from a nearby house, untied the horse, and rode it up and down the empty field. The boy was Miguel’s other son. Miguel didn’t speak to him, and the boy didn’t know Miguel was his father. Perhaps that has changed since Miguel’s death.

Miguel always wanted a son, says Guadalupe, and he got at least two of them, maybe three. The tragedy of Miguel’s life is that he lost them all. The first – if there is one in California – he gave up because of the realities of immigration and the penalties of his depravity. The second he traded away in exchange for marriage to Guadalupe, a barter that forced Miguel to spectate from a distance as the boy grew. The last, Kiki, watched Miguel die, unable to bid him farewell even from inches away.

A boy died in Mexico, taking with him the dreams of his father.