There are few combinations more morally toxic than youth, money and testosterone, especially when inflamed by the debauchery that universities tolerate at fraternities under the guise of tradition.

The behavior of frat house bad boys was once limited to the hijinks of “Animal House,” whose motley miscreants stopped at toga parties, shoplifting, and a Mrs. Robinson moment involving the lascivious wife of Dean Wormer.

These days, in an America plagued by drug abuse (legal and illegal), on campuses defined by economic elitism, and throughout a digitized world where the dark side of humanity lurks only a click away, binge drinking, brutal (sometimes fatal) hazing, and persistent stupefaction are as common among the Greek campus community as coats of arms.

This is the world Max Marshall found in 2016 when he began reporting a story about a “small-time” fraternity drug dealing ring at the College of Charleston in South Carolina. To his surprise, he found a massive interstate web of drug trafficking that involved millions of dollars, hundreds of thousands of pills like Xanax and Oxycodone, bricks of cocaine bought from a Mexican cartel, and a murdered student.

Once, says a writer quoted in the book, a “bro” meant “a self-absorbed young white guy in board shorts and a taste for cheap beer. But it’s become a shorthand for the sort of privileged ignorance that thrives in groups dominated by wealthy, white, straight men.”

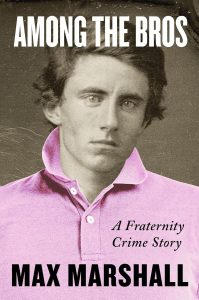

The dope-dealing bros of Kappa Alpha dressed in polo shirts and pastel shorts. Imagine Tony Soprano’s crew as Andover grads clad in Ambercrombie. They flouted the law and flaunted their audacity. Children of entitlement, their creed was (to borrow from the New York Times): “We will behave badly, and we will get away with it.”

Marshall graduated from Columbia University in 2016, the same year police arrested the ring. His youth and his background as a fraternity member (Delta Sigma) no doubt helped him gain access to the incarcerated kingpin, Mikey Schmidt, as well as to dozen of former College of Charleston students and frat members who in interviews portrayed the campus as “a country club for rich New Englanders.”

Marshall’s reporting is thorough and detailed. He puts you in the frat house, and what you see ain’t pretty. At times, though, he is too thorough. Some pages seem compiled from what we old-time newsies called a notebook dump. Facts make the story, but more of them doesn’t always make a better story.

Still, Among the Bros held my attention and it might hold yours as well if you’re wondering what the incoming generation is doing with the mess we’re leaving them.