What most surprised me in this thorough, readable biography of the narcissistic, bullying charlatan who captured the White House and then held the nation hostage for four years is how surprising I found his political success at the time. Had I been paying attention, as Maggie Haberman had through most of her career as a reporter in New York City and then in Washington, D.C., I would have seen Donald Trump coming – and so might have enough others to thwart his rapacious intentions.

It seems almost redundant to use the word revelatory to describe any book about Trump because he himself is an open book. As Haberman writes, he treats everyone he knows as “a chance for him to vent or test reactions or gauge how his statements are playing or discover how he is feeling. He works things out in real time in front of all of us.” However, Confidence Man is filled with revelations, at least for those us who never saw an episode of “The Apprentice”:

- The decades-long ties between Trump and the political puppeteers he employed as president such as Roger Stone and Paul Manafort (both convicted, both pardoned).

- Trump’s lifelong habit of deliberately exploiting hate and controversy: “I bring out the worst in my enemies and that’s how I get them to defeat themselves.” And: “I want to hate these muggers and murderers. I want them to suffer.” Thus answering the question: Is he the way he is by choice? Yes, partly.

- His instinct to simultaneously bloviate and obfuscate is purposeful: “Whatever complicates the world more, I do. It’s always good to do things nice and complicated so that nobody can figure it out.”

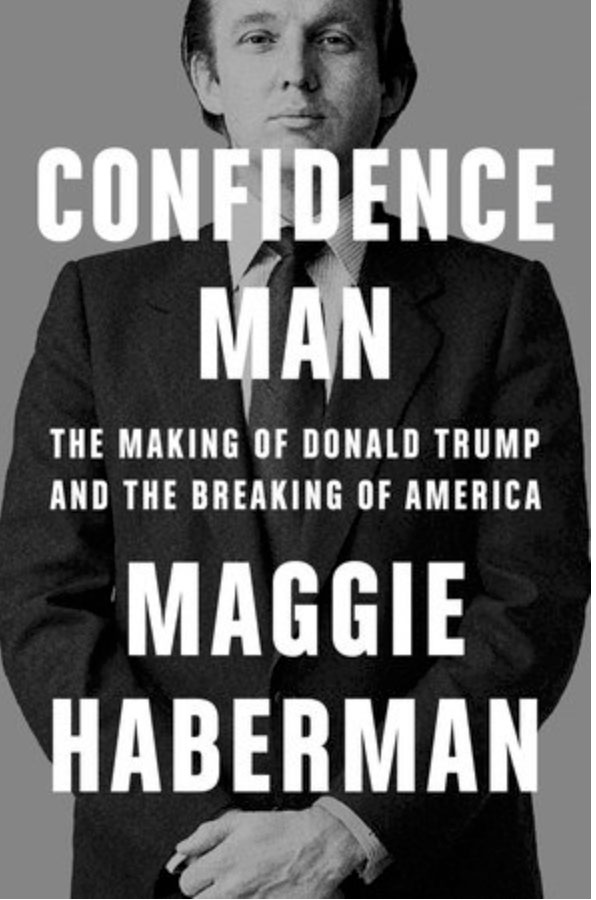

There are many books in print about Trump’s White House tenure, but of the few I’ve read – Bob Woodward’s Rage and Peril among them – Confidence Man tells the story of the craziness and immorality that characterized the period in the least breathless way, relying as it does on the solid reporting that won Haberman a Pulitzer, and, more importantly, wrapping all the self-serving shenanigans and the sideshow of characters in the context of Trump’s fundamental yearning to be recognized and rewarded.

In a post-presidency interview, Trump exposes this need, which Haberman describes as “for people to know who he was, and not merely to be rich.” He tells her: “The question I get asked more than any other question: If you had to do it again (run for president), would you have done it? The answer is, yeah, I think so. Because here’s the way I look at it. I have so many rich friends and nobody knows who they are.”

Sadly, the nation is not yet done with Trump. Even if he can’t rise out of the muck of Mar-a-Logo to despoil once more the Oval Office, he has sullied the American democracy with a stain that won’t be removed in the short term.

To Haberman’s credit, she acknowledges that despite her formidable reporting she cannot answer the question: Who, really, is Donald J. Trump? “I spent the four years of his presidency getting asked by people to decipher why he was doing what he was doing, but the truth is, ultimately, almost no one really knows him. Some know him better than others, but he is often simply, purely opaque, permitting people to read meaning and depth into every action, no matter how empty they may be.”

Trump remains afoot. We are forewarned.