Mosaic artist Rachel Rodi, right, helps volunteer Joanne Gordon at the the new Canal Community Garden

Far out on the edge of the Canal, past the blocks crammed corner-to-corner with parked cars, beyond the rows of sagging apartment houses packed with immigrants, on the other side of the new Mi Pueblo grocery, where Mexicans and Guatemalans and Salvordorans shop for sheets of chicharron, fat plugs of quesillo and other foods that make home seem less distant, far the from busy intersection where broad-backed men line up for day labor, not near any of those things, but on the long, low flat of fill that stretches to the Bay and one day will hold some brand of box store if the city fathers have their way but for today, at least, sits empty, they’re building a garden.

The Canal Community Garden, located on a quarter-acre of city land at Bellam Boulevard and Windward Way, is an array of 5-foot-by-10-foot, redwood-rimmed beds that, come next year, will abound with organic, herbs, fruits, vegetables and flowers, each plot the labor of someone whose desire to extract bounty from the land overcame the unlikelihood that they’d ever be able to do it in a place as infertile as the Canal.

Work on the garden began in September. Seeds go in the soil in February. When the first harvest comes, the urban farmers and gardeners of the Canal should thank The Trust for Public Land and the Canal Alliance for making it happen.

I was there on Saturday, talking with a Philip Vitale of the Trust for Public Land, the project manager. He filled me in: a budget of more than $600,000; 92 garden plots of various sizes; a greenhouse for sprouting; a storage shed with lockers; a central space for classes and education; and, centering it all, a circular mosaic celebrating the overlap of art, food and community.

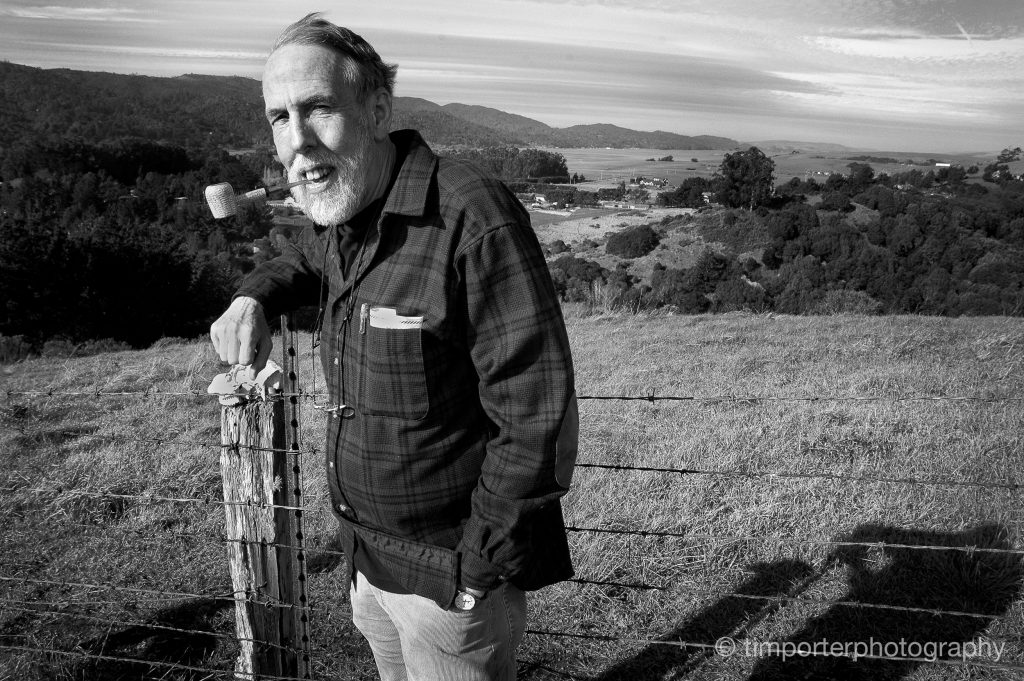

The mosaic came together while I watched. Oakland artist Rachel Rodi, the designer, and a half-dozen other women worked shoulder-to-should around a rectangular table, cutting sheets of blue, purple and green tile into shards of many shapes, laying beads of glue on the pieces and inserting them into the unfinished mosaic. It was a jigsaw puzzle with a twist: There were no pieces until someone made them.

The Canal Community Garden is the successor to one that was lost to the expansion of the Pickleweed Community Center in 2005. Since then, said Vitale, The Trust for Public Land has worked on a replacement. Partnering with the Canal Alliance, the neighborhood’s primary social service and advocacy organization, was key to the success of the project and ensures ongoing management of the garden, he said.

Daniel Werner, an AmeriCorps VISTA staffer on loan to Canal Alliance, is the garden coordinator. (To learn more about the garden or to apply for a plot, contact Werner at danielw@canalalliance.org, 415-306-0428.

I showed up at the garden on Saturday to scratch an itch, one that’s festered in the years I’ve been out newspaper journalism — a desire to feel the connection to community I felt when I first fell into photojournalism and, then, reporting.

As many did, I wandered into journalism by accident, but once there found enchantment and intrigue in the stories of ordinary people. I began as a photographer and loved capturing the faces of people with the camera. When I started writing, I became addicted to the interview, the act of questioning and asking why and how and who. I was nosy and I guess was needy and the conversation satisfied both.

Eventually, I let many of those things slip away. I managed people instead of photographing them. I wrote memos instead of stories. I looked far ahead and missed what was in front of me. I’d succeeded in the business of journalism, but I’d stopped honoring the passion that brought me to it in the first place.

Now, I’m, if not wiser, certainly older. I don’t confuse ambition with passion any longer. I recognize the difference between what I must do and what I love to do. I admire more the great storytellers, visual and written, and the work they do to bring those stories to us. And, perhaps with some regret – because we all have just a little, don’t we? – I wish I had made more of an effort to become one of them.

I didn’t, though, so I do this – stop by an empty city lot on a cold fall afternoon to meet a group of good-minded people who are building a garden, an enterprise that enriches the neighborhood, elevates the common welfare and rewards them with the individual satisfaction. I take some pictures, I ask a few questions, I find a small story and I share it. It is journalism with the smallest “J” possible. Not hard-hitting. Not world-changing. Not much of anything really other than a thin slice of truth, a small dollop of daily life, and a healthy reminder to myself that this is who I once was – and who I can be again.