One reason I like hanging out with ranchers is the simplicity of what they do: Raise animals, then sell them to the rest of us as food. As a basic business model, it can’t be beat conceptually.

Of course, there’s nothing simple about ranching these days. There’s the ever-rising costs of grain and land and gas. There’s the mega-ranches driving down milk and beef prices so low that smaller ranchers are cashing in good grassland for condo developments. And, there’s the work, the seven-day, crack-of-dawn-t0-last-light, never-ending work, a list of to-do’s that runs longer than the barbed wire around a 40-acre plot.

That means that family ranchers aren’t simple people either anymore. In order to have something more left at year’s end than a promise of another 365 days ahead like the ones just finished, something they can leave their kids with the hope that they’ll stay on the land, many small ranchers are now applying the same effort to expanding their businesses, eliminating the middleman and connecting with consumers as they always have to breeding their herds, compiling their silage and keeping the barn cats happy.

Dairymen are making cheese. Cattlemen are growing organic apples. Ranching families are leasing and to urban escapees who want to try their hands at something new, such as raising water buffalo in order to make mozzarella.

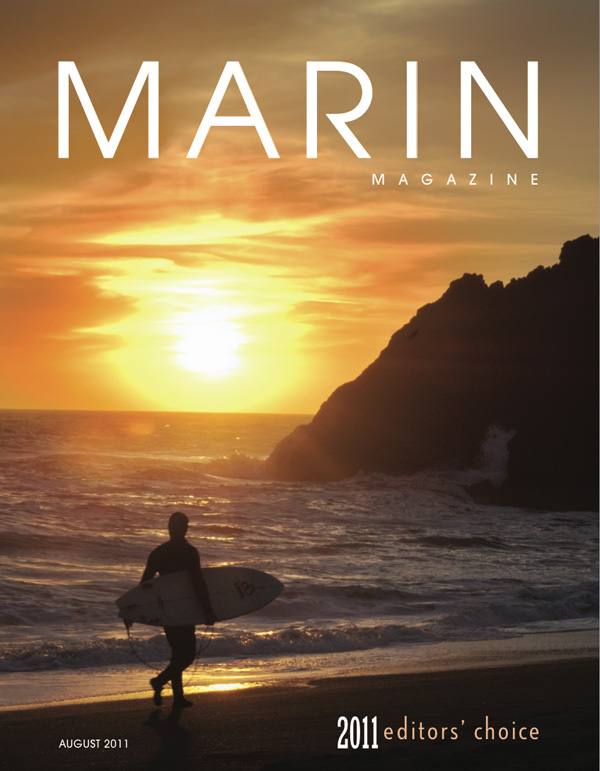

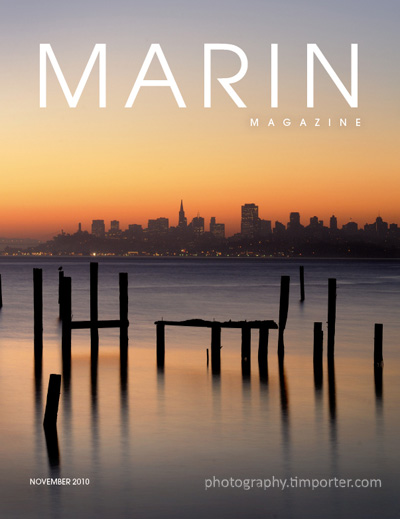

Marin County is a national leader in this sort of agri-innovation and for the current issue of Marin Magazine I had the opportunity to illustrate a story – reported and written by Inverness journalist Jacoba Charles – about how four local families are changing the concept of ranching.

In the course of shooting on the different ranches I got licked by a water buffalo (not so bad), had my index fingered suckled by heifer (more fun than I should admit) and more than once knelt in something soft and warm (hey, it’s organic).

Here are snapshots of the four shoots (the full story is here):

* Mike and Sally Gale’s ranch is on Chileno Valley Road, one of West Marin’s prettiest roads, undulates over 600 acres, plenty of room for the Black Angus cattle they raise and sell directly, butchered and freezer-ready, to grass-fed beef lovers. Since returning to Marin in 1993, the Gales have expanded the offerings of the Chileno Valley Ranch to pork, eggs and organic apples, pears and more.

* Bob Giacomini has been raising Holsteins in Point Reyes Station for more than 50 years, and is part of a sprawling farm family whose Swiss-Italian roots extend back 100 years in Marin and Sonoma counties. Ten years ago, Giacomini’s four daughters – Karen, Diana, Lynn and Jill – launched the Point Reyes Farmstead Cheese Company. Now, they’ve added The Fork at Point Reyes, a cooking school and event space located dab smack in the middle of the family’s 700-acre ranch overlooking Tomales Bay.

* What the Giacominis are to Point Reyes, meaning iconic and ubiquitous in name, the Lafranchis are to Nicasio. Fredolino Lafranchi, also a Swiss immigrant, began ranching in Nicasio in 1919. Today, his grandchildren still make milk, although now it’s organic, and use it as the base for a line of farmstead cheeses sold through their new Nicasio Valley Cheese Company. “We looked on it as a chance to allow the ranch to continue, because the dairy business has been really hard for the last 10 years,” said Rick Lafranchi.

* Craig Ramini has traded in the high-tech life of Silicon Valley and software consulting for the decidedly retro world of Tomales and cheese-making. Ramini leases 25 acres from longtime rancher Al Poncia that he’s using to raise Asian water buffalo, whose milk he’ll turn into mozzarella di bufala and sell under the name Ramini Mozzarella. Ramini is living out a new dream and Poncia is finding a way to sustain his family ranch.

Here’s what Poncia told the Marin IJ earlier this year in a story about Ramini’s plans:

“A long time ago, sometime in the late ’60s to mid-’70s, someone who was pre-eminent in the dairy business told me, ‘Al, agriculture in Marin County is dead.’ But I wanted my chance. And I’ve had it. And luckily, because we’ve held on up here, I’m now able to provide other people with that opportunity — including my son, who is working very hard with his grass-fed beef operation (Stemple Creek Ranch).

“And now Craig’s come along with his boutique cheesemaking plans, and I think that fits into where Marin, Sonoma and the whole Bay Area’s agriculture is going,” said Poncia, whose grandfather purchased his ranch in 1901. “Our ranch is now producing diversified products for a local market, which is something we haven’t been able to do for quite some years.”

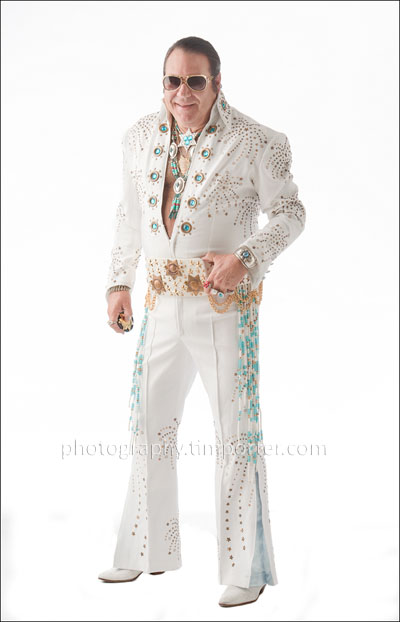

sometimes calls “photo crap” — i.e., gear — is involved in making what becomes a simple white background image when printed. Here there are five lights, three of which you can see and two others behind the black foam boards pointed at the background.

sometimes calls “photo crap” — i.e., gear — is involved in making what becomes a simple white background image when printed. Here there are five lights, three of which you can see and two others behind the black foam boards pointed at the background.