A whole fish – head, tail, bones and all – fried on the stovetop. A goat, butchered and sunk into an earthen oven for hours. Sides of beef and pork, killed just steps from the stove, slathered with chilies and roasted beneath avocado branches. Burgers, thinner than sliders, so light they go down like beef-flavored air. Ham-and-cheese sandwiches drenched in mayo. Refried beans rich with epazote. Carrots, peeled into transparent slices, bathed in lime juice. Chunks of jicama dusted with chili powder. Frosted slabs of tres leches cake, celebrating birthdays and graduations. Half-sized bottles of Corona. Shots of mescal. Tall plastic glasses of sugary soda, bright yellow and deep red, representing flavors not found in nature.

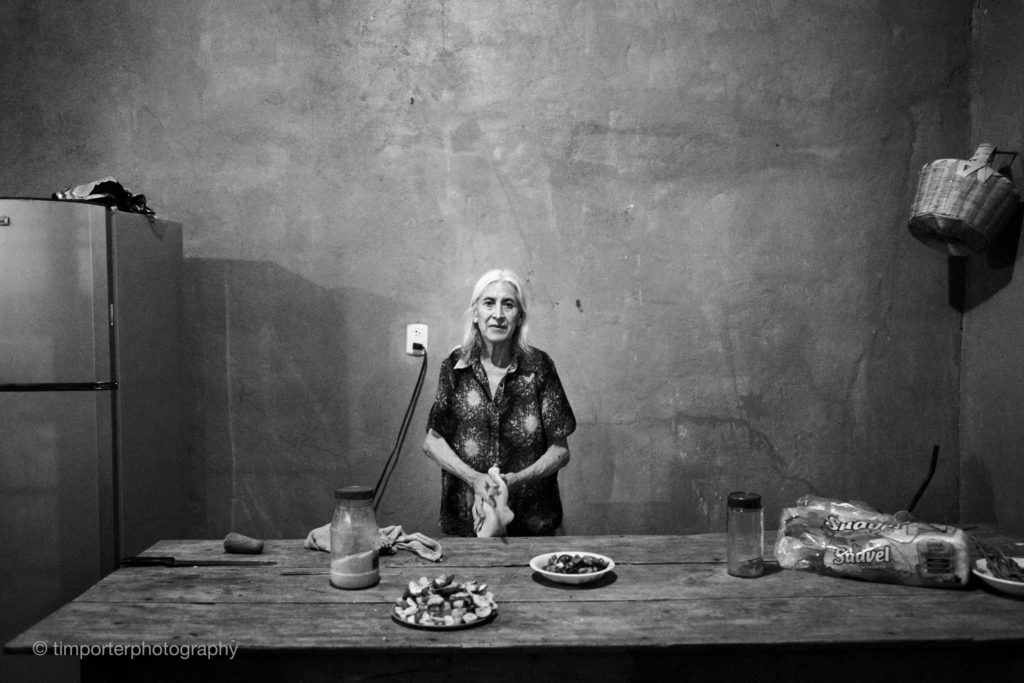

All the food in the Ojeda household passes from the hands of Maria and her daughters, Alberta and Guadalupe, to the mouths of family and friends – some from down the street and others, like a son long gone, from a country far to the north.

The Ojeda kitchen is long and wide and rises to the height of two men. A tall, arched window bounces daylight off its walls, which declare their cultural vibrancy in tones of unabashed pink. At night, the color fades into shadows, penetrated barely by the fluorescence of a single bulb and tinged, deliciously, with the lingering aromas of the day’s cooking.